Charles William Morrison

First Lieutenant

442nd Regimental Combat Team

3rd Battalion, L Company

Charles William Morrison was born on November 3, 1918, in Gotebo, Washita County, Oklahoma. He was the oldest of three children born to James Marshall and Esta Edith (Watkins) Morrison. His sisters were Mildred Pauline and Faye Virginia. Father James was born in Cloud Chief, Wichita County, Oklahoma; and mother Esta was born in Beaver, Nebraska.

By 1930, the family was living on Stringtown Road in Wichita County, Texas. Charles later said that his father “went broke raising cotton” in Oklahoma, so the family moved to Texas. Jim Morrison was a tractor driver for a crude oil company. Charles graduated from Fairview High School in Wichita County, Texas, in 1935. He then went to Gladewater in East Texas where he lived with an uncle and did odd jobs, while trying to get a job in the oil field. At his grandmother’s insistence, he attended Cameron Junior College in Lawton, Oklahoma, from 1935 through 1937, studying animal husbandry. He next went to Oklahoma State University in Stillwater (previously known as Oklahoma A&M) at his mother’s insistence to study mechanical engineering. While at A&M, he was in the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC). He later recalled that he did not do well in this field, so he dropped out of school in 1939. At this point, he had completed 3½ years of college.

Morrison spent some time trying to find a job, but jobs were scarce. He decided to go to California to pick fruit. On his way, he stopped in Hobart (western Oklahoma) where an aunt and uncle lived. They notified his mother that he was there, and she insisted that he return home. At this point, he was flat broke, and as he started to hitchhike back home, he was so hungry that for the only time in his life he begged for food. Knocking on the door of a house, he asked a lady for something to eat and she gave him a glass of milk with cornbread to tide him over. After arriving home, he got a job with the LaSalle Petroleum Oil Company. As the oil wells were being cleaned out, his job was to lie on the floor and break the tubes as they were pulled out, covering him in fuel. It was so bad that he had to take a “gasoline bath every night after we finished,” as he later recalled.

In 1940, the family still lived on Stringtown Road and Jim was an oil field roustabout, Esta was a nurse, and Charles worked as “relief” at an oil refinery.

On October 1, 1940, he married Pauline Alpha Turnbow, in Cotton County, Oklahoma. At the time, they were both living in Burkburnett, Wichita County, and they moved to 300 East Roosevelt. Pauline was born in Portia, Arkansas.

Charles registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, at Local Board No. 3 in Electra, Wichita County, Texas. At the time, he was living on Route 1 in Burkburnett and working part-time for the LaSalle Petroleum Corporation. Originally working in the oil fields as a roustabout, he was trained as an assistant lab technician and worked in the refinery. Later, he became a clerk in the corporate office. He listed his father as his point of contact. He was 6’½” tall, weighed 174 pounds, and had light brown eyes and black hair.

Morrison volunteered and was enlisted in the Army on November 19, 1941, at Wichita Falls, Texas. He was still employed by the LaSalle Petroleum Corporation in Burkburnett. He went through the U.S. Army Processing Center at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio.

Charles William Morrison went through basic training at Fort McIntosh in Laredo, Texas. Following basic training, he was assigned to the 8th Engineer Squadron, 1st Cavalry Division, and promoted to Technical Sergeant. In 1942, he was promoted to Sergeant Major.

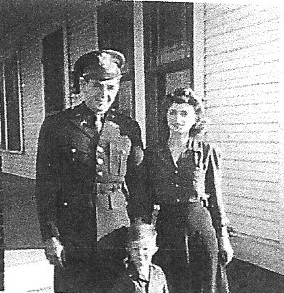

Right: Lt. Morrison with his parents and eldest son, c. 1943

In late 1942, Charles applied for Officer Candidate Training School (OCS) at the Adjutant General School. After not hearing for some time, he applied for the Infantry OCS and was accepted immediately and sent to Fort Benning, Georgia, where he was assigned to 2nd Company, 3rd Student Training Regiment. He eventually was accepted to the Adjutant General School, but decided to stay with the infantry. After thirteen weeks at OCS, he graduated and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant on January 9, 1943. He was assigned to the 51st Infantry Training Battalion at Camp Wolters in Mineral Wells, Texas. For nine months, he trained troops of the ammunition and pioneer (i.e., sappers and combat engineers) group for the infantry and later for two months was the Battalion Supply Officer.

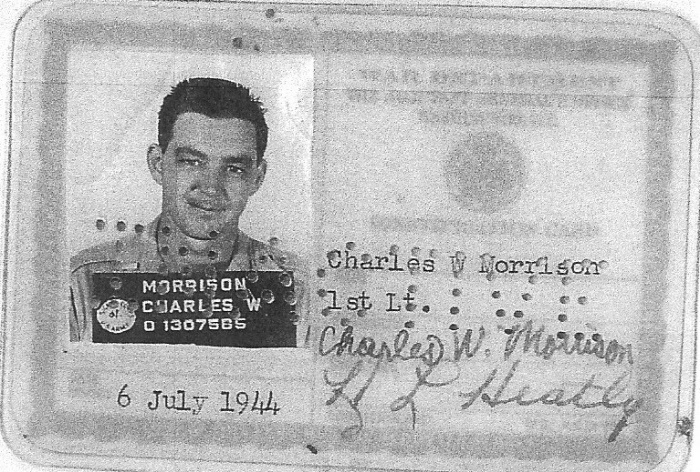

Left: 1st Lt. Charles W. Morrison’s Army ID card issued on July 6, 1944

Morrison was then transferred to Camp Gruber, Muskogee, Oklahoma, and promoted to First Lieutenant on November 29, 1943. He was the Supply Officer for the 42nd Infantry (Rainbow) Division, Headquarters Company. He became the executive officer and then a platoon commander of the Antitank Company in early 1944. He also served as Battalion Adjutant.

Right: Lt. Morrison with his wife and eldest son

In August 1944, Charles was assigned to the Replacement Depot at Fort Meade, Maryland, for overseas assignment. Replacements for American units in Europe followed various circuitous routes to reach their destination. Morrison later recalled the route that he took, outlined below.

After processing at the Replacement Depot at Fort Meade, he went by train to Boston, Massachusetts. He embarked on a troop ship from Boston Harbor on September 15, 1944, arriving on September 21 in Liverpool, England. There were three or four shiploads with replacements who landed there with all their equipment. Englishmen drove their trucks forty miles south to their staging area at Beeston Castle in Cheshire. After all their equipment was readied, the soldiers went by train to Southampton and were loaded onto a ship to cross the English Channel to France. They landed on Omaha Beach on the coast of Normandy. By this time, the beachhead had been secured and the fighting was further inland, so they were not under heavy fire as they landed. They again loaded onto their trucks and continued to Marseilles, avoiding Paris as it was still held by the Germans. Once in Marseilles, Morrison was assigned to the 442nd RCT, which was part of the Seventh Army. He met up with the 442nd which arrived in Marseilles on September 29 to join in the Rhineland-Vosges Campaign. Morrison was assigned to 3rd Battalion, L Company, as Executive Officer and 3rd Platoon commander.

The 3rd Battalion was moved from the staging area in Septèmes, just outside Marseilles, on October 10, by rail up the Rhone Valley north to the Vosges Mountains. They arrived in the assembly area at Charmois-devant-Bruyères at midnight on October 13. On October 15, the Combat Team attacked the important road center of Bruyères.

The town lay in a valley bordered by four conical hills that the Allies named A, B, C, and D. To take Bruyères, the 442nd had to take the hills. On October 15, the 442nd launched their attack. The Germans had the terrain and the weather on their side. The mountains were more than 1,000’ high and were covered with tall pines. The fog and the thick underbrush limited visibility to a dozen yards. For three days, the infantrymen fought back constant German attacks. With the help of artillery fire from the 442nd’s 522nd Field Artillery Battalion, the 100th Battalion took Hill A, and the 2nd Battalion took Hill B. The 3rd Battalion routed the enemy out of Bruyères, but the Germans still held Hills C and D until the 442nd captured these last two hills. The men began pushing the Germans north across a railroad embankment and toward the forested area of Belmont. It was here that a K Company soldier shot a German officer and captured a complete set of German defense plans.

Using the information in the defense plans, the 442nd’s Regimental Commander formed a Task Force comprised of Companies F and L, who at that point were reserve companies of the leading battalions. This group, known as the O’Connor Task Force, moved without detection during the night of October 20 to a position in the enemy’s left rear. At dawn of the 21st, the commander launched his attack after a preparation of prearranged fires controlled by a forward observer with the Task Force. F and L Companies, led by Major Emmet O’Connor, infiltrated the German lines during the night. At dawn they attacked the enemy from behind, while the 2nd and 3rd Battalions attacked in front. The men were aided by the pinpoint artillery fire of the 522nd. By mid-afternoon the Task Force and the Combat Team made contact, and whatever enemy troops were not surrounded were completely routed, thus bringing to a close a plan brilliantly conceived and expertly executed. By the next day, the Combat Team had secured the high ridge that dominates Belmont. For this action, they were awarded the Distinguished Unit Badge.

On October 23, the 442nd liberated the next town, Biffontaine. Finally, on October 24 they were taken off the front lines and put in reserve in nearby Belmont for a rest after eight days of heavy fighting, little to no sleep, harsh weather conditions, and many casualties.

On the afternoon of October 26, the short rest was abruptly ended when the 442nd was ordered to go into the lines the next morning and fight through to rescue the “Lost Battalion,” the 1st Battalion of the 141st (Texas) Infantry Regiment. After moving too fast and over-reaching its support, they had become surrounded on three sides by the enemy and were unable to extricate themselves. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 141st Infantry Regiment had tried to rescue them along with other units, but were thrown back each time they attacked.

The 442nd’s 3rd Battalion moved out at 4:00 a.m. on October 27. The men were forced to march in column, with each man holding on to the pack of the man in front of him, as they could not see each other in the darkness. By 2:00 p.m. they were in line with the other two infantry battalions of the 442nd. The attack moved slowly and encountered heavy resistance from enemy infantry and incessant mortar concentrations. The fighting was severe. All units resumed the attack on the morning of October 28, with resistance as fierce as ever. Third Battalion encountered a series of manned roadblocks in its advance up the hill, and L Company was stopped by enemy fire from several machine guns, riflemen, and grenadiers. The battle was finally won on October 30 and the Lost Battalion was rescued.

The next series of battles drove a wedge through the German line into the Valley of the Rhine and the German border. The fighting was fierce with heavy casualties. By November 9, almost all elements of the 442nd RCT had been relieved and pulled back to rest areas. On the afternoon of November 13, 3rd Battalion returned to the battle line to maintain a defensive line in the forest it had cleared in the previous fighting.

On November 14, Lt. Morrison led a combat patrol of 15 men. They left the Command Post located two kilometers northwest of Le Petit Paris, vicinity of Chevry, at 1:00 p.m. by vehicle to Chestel, where they dismounted and moved up to clear the houses near Le Petit Paris. When they approached the farmhouses, about 15 Germans, barricaded in the houses and dug in around them, opened fire with machine guns, rifles, and mortars. A severe firefight ensued and L Company suffered casualties. Five men were wounded: Pfc. Arthur Kaisaki, Pfc. Goro Nagasako, Pfc. Albert Ohama, 1st Lt. Charles W. Morrison, and Pfc. Mitsuru Hayashi. And two men were wounded and captured: Pfc. Masao Ikeda and S/Sgt. John Hashimoto. Tech Sgt. Masaharu Okumura later described the patrol.

“[Tech] Sgt. [Kankichi] Nakama came up to us and said he needed men for a patrol to clear some houses for G Company men to sleep in that night. He selected fifteen men of whom I was one. I told him my 536 was useless because of the rain and we had no batteries for it. He said there wasn’t one in the whole regiment, so we went without. …we passed through the G Company area… He went down the hill from G Co. area and located a farmhouse. First Lt. Morrison, who was leading the patrol, and I reached the corner of the building, with Mits Hayashi holding down the other. The rest of the patrol was entrenched in a gully running parallel to the house just about 20 yards above us. The Lt. peeked around the corner and just at that moment I saw a door open and a German stepped out halfway. The Lt. hurriedly opened fire, missing the German entirely. He said, “I’ll be right back” and disappeared up the hill. A firefight started, but Hayashi and I were up against the farmhouse so we couldn’t see anything but listen and wait for our leader to come back. After a while we got the word to withdraw because the Lt. was hit in the head. Mits and I withdrew to the gully and found two of our men dead or dying. No one knew what to do, but I found another gully which went straight up the hill and told the men to hug the right side as we went up. Sure enough, the enemy had the gully sighted in and we could see the tracer bullets shooting right up the center. It was dark by now and visibility was limited. We came across the Lt. halfway up and I sent the men up while I tended him the best I could. He was shot in the head and was delirious. I found out later that he was going after a bazooka, but he never told me about it….We were recommended for a medal for that day “for military valor and achievement.”

And Morrison later recalled:

“…those kids…all they knew to do was to fight and so they didn’t give up. Then I tried to get one of these machine gunners. He didn’t want to surrender. He just turned his gun on me and that’s when I got hit. My patrol came and got me – well, they captured this kid that was on the machine gun and then they came and got me. They had to strap me on the stretcher to get me back because I kept trying to get off. Then they took me back and I was in a field hospital near Bruyères. An old hotel is what I was in. That’s where they had the hospital. I stayed there until they thought, “Well, I guess you’re going to live,” because then they proceeded to send me back to the states. So, I was put on a train and I went down to Marseilles.“

Morrison had suffered a severe head wound from a single shot to his temple that exited in the right occipital region. He was recovered from the battlefield by his men and taken to a field hospital near Bruyères. He later recalled to his family that he was proud of the fact that his men carried him to an aid station after he was wounded. His wounding was reported in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram on December 8.

Upon regaining consciousness three weeks after his wounding, Lt. Morrison had considerable loss of vision and a near-total loss of hearing, which gradually improved as did his persistent headaches.

Morrison saved the hand-drawn Christmas card for the menu for the patients’ dinner on December 25, 1944. They were served the traditional roast turkey, dressing, mashed potatoes, giblet dressing, buttered green beans, cranberry sauce, rolls, and mincemeat pie.

(Left: Front cover and inside of menu)

On January 9, 1945, 1st Lt. Eugene D. Harrison of L Company wrote to Morrison expressing the best wishes of the men and officers for Morrison’s hard work while with them. The letter stated that “we were very sorry to have you get hurt, as well as lose you as an officer.” He noted that Capt. Roger Smith and Lt. Shoichi Koizumi were still with the company and getting along fine. Harrison wrote that he would send Morrison’s stuff to him as soon as possible and Morrison could send money to Koizumi if he wished.

It was two months before Morrison could be returned to the States by ship. On January 23, 1945, he left France on the U.S. Army hospital ship USHS Charles A. Stafford to Charleston, South Carolina. On the ship, he got word that another 442nd soldier wanted to see him. As he later recalled, it was his platoon sergeant, Staff Sergeant William C. Oshiro. In Morrison’s words:

“Willie had stepped on a land mine and lost his leg. So, he filled me in a little bit on what had happened.“

Oshiro was wounded in Sospel at the beginning of the Rhineland-Maritime Alps Campaign soon after leaving the Vosges. He had received a promotion to Second Lieutenant.

Morrison’s ship arrived in South Carolina on February 5 and he was admitted to Stark General Hospital in Charleston. His recollection continued:

“When I landed in Charleston, all I had was a pair of hospital pajamas and a robe. That was all the clothes that I had. So, the first thing that I did, I wanted some clothes, but they wouldn’t give me any. So, I went to the quartermaster and I told him my situation and that I wanted some clothes. At first, he wasn’t going to give them to me, but I was going to go over his head anyway if he didn’t. Then he decided to give me some clothes and so that’s how I got my first clothes when I got back to the States.

I stayed there for about a week or ten days and then loaded on a train and came to California, to Santa Barbara. They were supposed to check my eyes and my hearing. I’d lost part of my eyesight and part of my hearing. They did. I stayed up there for a couple of weeks…They decided they couldn’t do anything for me at that particular time. So, then they loaded me on the train and sent me back to Temple, Texas, to the general hospital there. Temple is where they repaired me. Finally, they let me out.“

Morrison had been moved by train on February 12 to Hoff General Hospital in Santa Barbara, California, arriving on February 16. He was next transferred to McCloskey General Hospital in Temple, Texas, on April 1. On April 13 he underwent an operation known as a “tantalum cranioplasty” and a metal plate was placed in his head. On June 8, 1945, he appeared before an Army Retirement Board. He was discharged from the hospital on June 10 on terminal leave.

Morrison was medically retired from the service on July 27, 1945. He soon began to suffer from seizures and was returned to McCloskey General Hospital where, according to his family, the silver plate in his head was replaced with a stainless steel one.

For his military service, First Lieutenant Charles William Morrison was awarded the Bronze Star Medal with one bronze oak leaf cluster, Purple Heart Medal, American Defense Medal, American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with one bronze star, World War II Victory Medal, Distinguished Unit Badge with one oak leaf cluster, and Combat Infantryman Badge. The two Distinguished Unit Badges were awarded for his participation with L Company and 3rd Battalion in the O’Connor Task Force on October 21, 1944, and the rescue of the “Lost Battalion” on October 24-30. He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal on October 5, 2010, along with the other veterans of the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team. This is the highest Congressional Civilian Medal.

After the war, Charles returned to Electra to work with the National Supply Company as an assistant store manager in the oil field supply business. Due to his war injuries, however, the company determined that he was not insurable and they dismissed him from his job. He enrolled in Midwestern College in Wichita Falls and the family moved to Burkburnett from where he commuted to school. The family then moved to Stillwater where Morrison attended Oklahoma A&M where he graduated in 1952 with a Bachelor’s degree in Agricultural Education. Two years later, they moved to Des Moines, in the northeast corner of New Mexico, where he took a teaching position in vocational agriculture at the high school.

In 1969, Charles earned a Master’s Degree in Agricultural Education from the New Mexico State University in Las Cruces. The Morrisons next moved to Moriarty, 40 miles east of Albuquerque. Charles was employed at Moriarty High School, where he taught vocational agriculture. He retired after nearly 30 years as a teacher and supervisor of Vocational Agriculture in New Mexico. He was active in Rotary International and the Moriarty Methodist Church.

Charles William Morrison died on December 18, 1998, in Albuquerque. His funeral was held at St. Paul’s United Methodist Church in Albuquerque. He was buried in the Santa Fe National Cemetery, Santa Fe, New Mexico, Section X, Site 596. He was survived by his wife, two sons – Charles Randall and William Patrick, one daughter – Sharon Ann, and nine grandchildren. His wife, Pauline Turnbow Morrison, died in 2009 and was buried next to her husband.

Morrison recalled to his family that he was proud that his World War II service had been with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Son William Patrick Morrison is a member of the Sons & Daughters of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Researched and written by the Sons & Daughters of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team with assistance by the Morrison family in 2021. The recollections quoted in this bio are part of an interview Morrison gave on December 29, 1996, to his brother-in-law and fellow World War II veteran Shirley Vernon Casey. The interview tape is on file with the Commemorative Air Force in Midland, Texas.