Masao Fujioka

Private First Class

442nd Regimental Combat Team

3rd Battalion, K Company

Masao Fujioka was born March 17, 1924, in Waihau, Kau District, Hawaii island, Territory of Hawaii. He was the son of Kamezo and Yasuko (Yoshimura) Fujioka. There were three sons and seven daughters in the Fujioka family. His siblings were : brothers Nobuichi and Francis Shigeo; sisters Haruko, Helen Fumie, Mildred Tamayo, Yoshiko, Sueko, Kikue, and Natsue.

In 1940, the family was living in Hilea, Kau District, and father Kamezo was a coffee farmer on his own farm. He had arrived in Hawaii in 1897, from Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan. Mother Yasuko arrived on March 19, 1915, from Ozemura, Yamaguchi Prefecture.

Mas, as he was known, signed his draft registration card on June 30, 1942, age 18, Local Board No. 6 in Pahala. His point of contact was his sister, Miss Mildred Fujioka of Pahala. He was employed by the Hawaiian Agricultural Company and lived in House No. 43, Mill Camp, Pahala. He was 5’5” tall, and he weighed 130 pounds.

In early 1943, when all eligible Nisei men were asked to volunteer to join the Armed Forces, Masao’s parents asked him to wait a year as he was only 18 years old and they felt that he did not fully understand the reason behind the voluntary service. He complied with their request.

Masao enlisted on August 17, 1944. His civilian occupation was listed as “Skilled mechanic and repairman, motor vehicles.” He was sent to Camp Fannin in Tyler, Texas, for his 15-week basic training that consisted of simulated battlefield conditions, small arms artillery, camouflage, and anti-personnel mines, defending against poison gas, and hiking with a full pack containing a 25-pound weight. Among his fellow trainees were mainland Caucasians and Hawaii men of all ethnicities.

Many years later, Masao’s daughter wrote about her father’s experiences. Her words about his training, shipment to Europe, wartime experiences, and occupation duties are below.

Masao spent many weekends in the city of Tyler with his two buddies. They would hustle a bottle of black market whiskey from a taxi driver for $10. There were no bars in the area, but bottles of liquor could be taken into restaurants. The three of them would catch a bus back to camp in the wee hours of the morning. They trained hard and tried to compete in everything. Masao remembers it was either the “wrong” way or the “military” way.

Training ended in December [1944] after field training out in the cold on Christmas Day. About this time, Masao learned that the Germans started a massive counterattack in Belgium [the Ardennes Offensive], which became known as the Battle of the Bulge. The Nisei trainees were left behind, but all the others were shipped out.

On New Year’s Day [1945], Masao left camp by train and headed east on a 10-day pass. A group of them chose to go to New York City over Chicago. The men were ordered to report to Fort George Meade in Maryland when their furlough was over. Again, they rode rail cars driven by steam engine, but these were much more comfortable than the one he rode into Texas.

Finally, the day arrived for them to head overseas to a destination unknown. Several times a night the alarm would go off for a submarine alert and Masao would walk up to the deck of the ship. They finally reached their destination and were told it was Le Havre, France. Some areas were totally destroyed, and in other areas steel helmets belonging to both Americans and Germans were scattered everywhere. The soldiers traveled south in “catch” cars. Since there were no seats, it was an extremely uncomfortable ride because they couldn’t stretch their legs, since it was too crowded.

After several days, the soldiers were dropped off in Marseilles. Masao pitched his tent and, to his surprise, he was in the same area as the 442nd Regiment. [Note: The 442nd arrived from Nice to the staging area in Marseilles on March 17 to 19.] Most of them had friends in this group and Masao decided to pay the 442nd Regiment a visit. Masao saw several of his hometown friends and everyone was happy to see each other after what seemed like many years of separation; actually it had been just 14 to 15 months. Masao knew they were replacements for the heavy casualties the 442nd sustained while fighting in [the Vosges Campaign in] France.

They deployed to Northern Italy [on March 20 to 22 for the Po Valley Campaign]. Masao had originally been a member of Company E, 2nd Battalion, but he had been transferred to Company K as a replacement. Masao’s first campsite was in an olive grove. The men were sent to the front lines as needed. In April 1945, it was still cold since they were up in the hills. He was posted in a foxhole guarding a position for the night. He shivered all night from being both scared and cold. At daybreak the troops were assigned to overtake a village below. Masao was told by his squad leader that each of them would look after each other, and after the mission he recalled seeing only one casualty on their side. The platoon took over several more villages and soon the war ended.

Although going home was the main topic of conversation for the Americans, it was not so for the Germans. When the war ended, thousands of German prisoners of war had to be dealt with. Instead of going back to their homeland, they were imprisoned in a stockade surrounded by barbed wire in Livorno, Italy. Germany could not accept their prisoners because the conditions in that country were so poor. Many members of Masao’s platoon felt sorry for them.

Right: Mas in bivouac during the Occupation

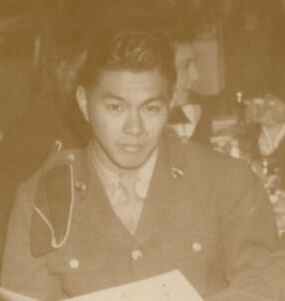

Left: Mas in Livorno, 1945/46

At this time, Masao’s platoon did mostly security work, processing German prisoners of war and serving as prison sentinels. It was relatively easy work because the Germans were model prisoners and were very well-disciplined. The prisoners would not even take cigarette butts without asking first. The prisoners prepared their own meals with food provided by Allied nations and performed daytime duties like working in the U.S. Army Food Supply Center, collecting and emptying the platoon’s trash cans.

As time went by, the soldiers found new friends among men they once called enemies. Often the sentinels would leave their cigarette butts in the cans knowing that the prisoners were glad to have them. The sentinels would purposely leave cigarettes and candy on their bunks before leaving their quarters so prisoners who came through would find them. There was a prisoner who for several cigarettes would prepare a bundle of firewood for Masao so that he could stoke the heater in the watch tower. The prisoner would whistle, and Masao then lowered a rope to haul up the firewood.

Above: Mas enjoying a meal, during the Occupation

When the German war prisoners were finally allowed to go home in small groups, the war was truly over. Before leaving Europe, many of the soldiers were allowed to visit different places nearby. Masao took advantage of the opportunity and had a particularly enjoyable vacation in Switzerland. In December 1945 while in Livorno, he was admitted to the station hospital with acute tonsillitis. After recovering, he was returned to duty. [This ends his daughter’s narrative.]

Left: Mas with his camera, during the Occupation

For his service, Private First Class Masao Fujioka received the Bronze Star Medal, Good Conduct Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with one bronze star, World War II Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal, Distinguished Unit Badge, and Combat Infantryman Badge. He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal on October 5, 2010, along with the other veterans of the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team. This is the highest Congressional Civilian Medal.

On July 10, 1946, Masao was among the returning veterans who arrived at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, from Europe for deactivation. On July 15, they marched down Constitution Avenue in Washington, D.C. to the White House Ellipse, where President Harry S. Truman presented a Distinguished Unit Citation.

Right : Mas at Iolani Palace August 9, 1946

Mas departed Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, on the USAT Waterbury Victory for Honolulu, arriving on August 9. This ship was met at the pier by musicians and hula performers and the 240 soldiers were each given fresh lei made by the community.

They were taken in a 60-car cavalcade down Dillingham Boulevard and King Street to Iolani Palace where they were greeted by Col. Farrant L. Turner (first Commander of the 100th Infantry Battalion), the Royal Hawaiian Band, and hundreds of family and friends for a welcome home ceremony. They were, then, sent to Schofield Barracks for their official discharge from the U.S. Army.

Left: Mas with sister Mildred, August 9, 1946

Once Masao returned to Honolulu, he met up with a fellow 442nd member from his hometown of Pahala. They reminisced about some of their friends who had been killed in various battles during the war. It was a tearful farewell when Masao and his friend parted ways.

After his discharge, Masao was employed as a mechanic at a garage on Punchbowl Street. He returned to Pahala in January 1947. On February 14, he sailed on the S.S. Matsonia from Honolulu to Los Angeles, where he attended the Allied Mechanics School on the GI Bill.

On November 10, 1951, in Pahala he married Teruko Yamamoto of Hilo. They settled in Honolulu and raised a family of three sons and one daughter.

Masao Fujioka died on March 14, 2015, in Honolulu. He was a retired general supervisor for the Hawaiian Dredging & Construction Company. Masao was survived by his wife Teruko, three sons, one daughter, two grandchildren, and two sisters. He was inurned in the Columbarium at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at Punchbowl, Section C11-P, Row 200, Site 244. Masao’s wife died on April 6, 2019, and is inurned with him.

Researched and written by the Sons & Daughters of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, with assistance from the Fujioka family, in 2021.