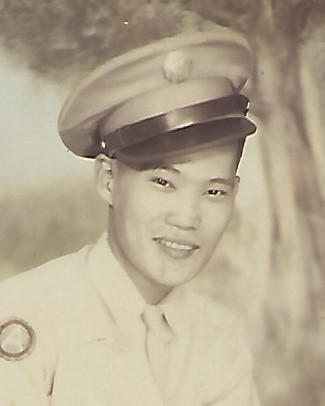

Thomas Takashi Nakahara

Private First Class

442nd Regimental Combat Team

Medical Detachment/Company G

Thomas Takashi Nakahara was born on February 16, 1923, in Paauilo, Hawaii island, Territory of Hawaii, to Minezo and Kiyo (Kawamoto) Nakahara. Minezo arrived in Hawaii from Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan, in 1894 at the age of 14. In 1902, Minezo was one of the founders of the Jodo Mission in Hakalau. He also founded the first Japanese language school in Hawaii at Hakalau. He lived in Hakalau for ten years prior to moving to Paauilo. In 1907, Kiyo arrived from Yamaguchi Prefecture, and she and Minezo were married. There were eight children in the Nakahara family: brothers Shoichi, Jiro, and Stanley Yuichi; sisters Sayoko, Kimiko, Masako, and Shigeko.

In 1930, the family lived on Government Road in the district of Hamakua. In 1940, Minezo was the proprietor of a retail grocery store; the only children still living at home at that time were Shoichi and Yuichi.

Thomas signed his draft registration card on June 30, 1942, Local Board No. 3 at the M.S. Botelho Building in Honokaa. His point of contact was his father, Minezo, and their address was P.O. Box A, Paauilo. He worked at the M. Nakahara Store in Paauilo, and also at Union Mill in Kohala.

Tom, as he was known, enlisted in the U.S. Army on March 18, 1943. At the time, he was employed as a sales clerk. Two days prior, he was among the 26 Nisei men who were honored with an aloha ceremony at the Kohala Theater in Halaula. The emcee was J. Scott Pratt, manager of the Kohala Sugar Company. Hawaiian and patriotic music was enjoyed by over 700 attendees. His mother gave him the traditional Japanese good-luck piece for soldiers going to war – the senninbari, a white cotton belt with 1,000 stitches in red thread, each sewn by a different woman. In later years, Tom related how his father was proud that he had enlisted, but told him not to bring shame on their family, community, or country. “Shinaru nara, otoko rashiku shine,” he said, which translates to, “If you’re going to die, die like a man.”

He was sent to Boom Town, the “tent city” at Schofield Barracks where the new soldiers were housed. On March 28, they were given a farewell aloha ceremony at Iolani Palace prior to departing on April 4 for San Francisco on the S.S. Lurline. Then followed a train trip across country to Camp Shelby, Mississippi. When he was issued his dog tags, Tom was labeled “P” for “Protestant,” although he had declared that he was Buddhist. After further processing, Nakahara was assigned to 2nd Battalion, G Company. Soon, however, he was disappointed when he was reassigned to the 442nd Medical Company. He received his medical training at the Surgical and Medical Technician School with several other 442nd Medics at Brooke General Hospital at Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas.

His father, Minezo, was imprisoned in a POW camp in Hilo in 1943-1944 for about ten months, while his brother Shoichi was imprisoned at the internment camp at Sand Island in Honolulu for two years. Tom complained about the unfairness of this to the 442nd Chaplain, who promised to take it up with the War Department.

After nearly a year of basic and specialized training and field exercises, the 442nd left for Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia, on April 22, 1944. On May 2, they departed from nearby Hampton Roads in a convoy of over 100 ships. They arrived at Naples, Italy, on May 28, marched to the train station, and were taken to Staging Area No. 4, about ten miles away in Bagnoli.

The battalion spent a week in Bagnoli before leaving on LSTs for Anzio on June 6, where they marched five miles to a bivouac area. From Anzio, the 442nd went to a larger bivouac area near Civitavecchia, north of Rome, where they went through additional training and final preparations for going to the front lines.

The 442nd entered combat on June 26 near Suvereto in the Rome-Arno Campaign. At the time, Nakahara was assigned as the medic for Headquarters Company of the 2nd Battalion. He later recalled how hard he worked that first day. In his words:

We were in a dry river bed and were shelled by the Germans. I was very scared. I thought I was going to get killed that first day. I never saw so much blood in all my life. I felt weak, but I knew I had a job to do and had to do it. I carried them back to the aid station. Sgt. Hayashi was giving orders, but others were shouting orders too. The aid station was completely in chaos.

By early July, he was reassigned as the medic for G Company, his old company from Camp Shelby. He told the company commander, Captain Jack Rodarme, that he did not want to be a medic – he wanted to be a rifleman. However, Rodarme replied he would be the company’s aid man and that was it. He described the heavy fighting at Hill 140, a major battle for the 442nd as they pushed the Germans north along the west coast of Italy. Many men were hit in one artillery barrage and the medics needed those left to hold the line so they could evacuate the wounded to the aid station. It was too far away and some were dying before reaching it, so Nakahara suggested it be moved closer. Men that he recalled helping as litter bearers that day were Tosh Narimatsu and Willie Thompson.

Soon after this action, Nakahara suffered a leg wound, but was able to return to duty right away. Second Platoon was asked to go north to Pisa on a combat patrol to check for enemy observation posts and the status of bridges across the Arno River. All eighteen men had volunteered and Nakahara also volunteered to go with them. The mission took three nights and two days and they made it back safely. They were recommended by Capt. Rodarme to receive a Bronze Star Medal, but it was later announced they would receive a Divisional Meritorious Citation instead. It was presented in a large ceremony while the 442nd was on rest leave at Vada.

Nakahara served in all battles of the 442nd in the Rome-Arno Campaign. The Combat Team then left for France on September 27. Once they arrived in Marseilles, they were in a bivouac area in nearby Septèmes until October 9, when they were transported north to participate in the Rhineland-Vosges Campaign.

In October-November 1944, the 442nd liberated the important rail and road junction of Bruyères, followed by Belmont and Biffontaine and the famous “Rescue of the Lost Battalion.” This was the 1st Battalion of the 141st (Texas) Infantry Regiment that had advanced beyond its support, become surrounded by the enemy, and was unable to extricate itself. Nakahara was wounded in France and this was reported in the Honolulu newspapers on November 22.

Nakahara’s recollections about his time in the Vosges Campaign include the following:

When we got to Bruyères, we encountered mortar, artillery, and machine gun fire. It was one of the most terrifying experiences for me. We were fighting in a forest with trees 60’ to 70’ high, and when enemy fire hit the treetops, there was no protection. Shrapnel rained down into the foxholes. Although it was fall, there were no fall colors, only mud and snow. As we dug our foxholes on the slopes, water oozed into the hole and we had to cut branches from pine trees as matting to keep dry and warm.

Without taking our shoes off for four to five days, many of us felt the stinging pain of trench foot without realizing the effect of cold, damp leather boots. We never washed our faces, shaved, or brushed our teeth.

The aid station was a few miles away and we were disoriented as to its location. The regimental aid station had a tent and was easier to locate, but the battalion aid station didn’t. The seriously wounded were carried on jeeps with two litters on each side and taken to the Division Field Hospital for immediate medical attention and surgery. We had morphine “syrettes” to use on the seriously wounded, except for those with head injuries.

First Lieutenant White…was hit by an artillery shell that hit his back…I gave him a morphine shot and bandaged him. I learned later that he died from his wounds. A few hours later, I remember attending to six to seven guys hit during an intense fire fight. I ran from tree to tree like a jackrabbit, giving medical attention. I remember a soldier also wounded by the railroad tracks. Somebody yelled, “Medic!” He was bigger than me, but I pulled him back under machine gun fire. I was wounded before that without knowing. I thought I had pissed in my pants. I put my hand in my pants and when I pulled it out there was blood. It wasn’t a deep wound, but I bled like a pig. I went to the field hospital near Epinal…For myself, I didn’t care if I “make” (Hawaiian for “die”). I was so tired and saw so many people die. I did my duty for my country, but the Second Battalion boys really needed me. They called me the crazy medic.

Somebody wrote me up for a Silver Star…I felt deeply that it was these boys who were doing the fighting that deserved a much higher medal than I. They displayed guts and absence of fear whenever they were asked to advance forward in combat…stoic courage.

For his gallantry in action in the Vosges, Nakahara was awarded the Silver Star. The citation stated in part:

When the company to which Nakahara was attached as aid man attacked the enemy, it received instant concentrated small arms, bazooka, rifle, and grenade fire. Two men were seriously wounded and lay exposed to the enemy. Although Nakahara was wounded in the hand by a shell fragment, he refused to go back to the aid station, and started to aid the two casualties in full view of the foe, who fired at him regardless of his Red Cross brassard. He proceeded to carry the two men to safety. He administered first aid and effected the evacuation of the casualties to an aid station. Nakahara’s courage and devotion to duty, which saved the wounded men from possible loss of their lives, reflect great credit on him and the best traditions of the armed forces.

Following the Vosges and his time convalescing in the hospital, Nakahara joined the 442nd for participation in the Rhineland-Maritime Alps Campaign in Southern France. They were in the area of Nice, Menton, and Sospel beginning on November 21, 1944. The mission was to protect the east flank of the 6th Army Group and guard against an improbable, although possible, enemy breakthrough down the southern coast of France. If the Germans had attacked in sufficient strength, there was nothing to stop them between the border and Marseilles, except the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Below and left: Nakahara in the Maritime Alps, 1944

To reach his unit high in the mountains, he recalled that he:

climbed the hills in Sospel with partisans and a mule-pack train. I hung on to the tails of the animals because the terrain was so steep. I rejoined my Second Platoon in a storage area for animals – a thatched grass hut on the hill. We had comfort and privilege, eating powdered eggs fried on a makeshift stove outside. The stone hut thatched with grass was about 10’x12’ and warm.

On March 13, he was awarded the Good Conduct Medal at a ceremony in France. On this same day in the Hawaii Tribune-Herald, it was reported that Nakahara was on a list of promotions of men in the 442nd. He was promoted to Private First Class.

The 442nd returned to Italy on March 25, 1945, for the Po Valley Campaign, leading to the end of the war in May.

The Combat Team’s presence in Italy was a closely-kept secret as their mission was to conduct a diversionary attack on the western anchor of the Germans’ Gothic Line, an elaborate system of fortifications hewn out of solid rock and reinforced with concrete. The enemy’s positions were built for all-around protection and observation. On March 28, the Combat Team left their Pisa staging area and moved to a bivouac at San Martino, near the walled city of Lucca. The move was made in absolute secrecy and under cover of darkness. While in bivouac, they went through more training – with the new replacements, who had seen little or no combat, practicing small-unit problems with their squads and platoons far into the night.

In April 1945, during the Po Valley Campaign, Nakahara was wounded in battle when an artillery shell wounded his hand. After being treated at an aid station, he was returned to duty.

His recollections of the Po Valley Campaign follow:

We climbed this steep cliff in the night…We kept our noses to the ground and the boys had the whole ridge in control after 12 to 14 hours…We walked into a trap. There was a slight depression where the Germans had two heavy machine guns with others carrying machine pistols. We got caught in a triple crossfire and fifteen guys in my platoon died, with nine wounded. It was late afternoon. I was on the ridge and our boys were on the bottom. I could see the Germans firing at them. The battle lasted about three hours with the First and Third Platoons helping us. There were many acts of heroism. Pfc. Robert Kishi…died in my arms. At one point, somebody yelled, “Medic!” It was “Onion” Ishida, a good friend. When I went to him, I saw he didn’t have a chance. I did what I could for him.

The surrender of the German army in Italy occurred on May 2, 1945. Nakahara said, When the war ended, I felt sad thinking of all my comrades who died, and wished they were with us to see the final outcome of victory and the glory. He was sent with the 442nd to Ghedi Airfield where they performed such occupation duties as processing and guarding prisoners. As he had over 85 points, he was eligible to go home. After a goodbye party with the Second Platoon outside of Brescia, drinking cognac and wine, he flew to Naples on June 11. At the airfield just prior to the flight to Naples, an award ceremony was held for the 200 departing men. It was during this ceremony that Nakahara was presented his Silver Star earned in France.

On July 29, he participated in a farewell ceremony and parade for 204 enlisted men prior to their shipment back to the US. Nakahara was among this group, the fourth group of soldiers to leave.

After arriving home to Hawaii, he was discharged on November 20, 1945, at a U.S. Army Separation Center on Oahu.

For his military service, Private First Class Thomas Takashi Nakahara was awarded the Silver Star Medal, Bronze Star Medal, Purple Heart Medal with two oak leaf clusters, Good Conduct Medal, American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with four bronze stars, World War II Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal, Combat Medic Badge, Division Citation, and Distinguished Unit Badge. He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal on October 5, 2010, along with the other veterans of the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team, which is the highest Congressional Civilian Medal.

In January 1948, he married Bernice Nobuko Uyehara in Paauilo, where they settled. They raised a family of one daughter and one son.

Tom wanted to become a doctor, but his father asked him to run the family stores. He later went into the insurance business and then became a real estate appraiser and realtor in 1962. At one point, he served as President of the National Association of Real Estate Appraisers. In 1972, he organized a group to purchase 3,000 acres of land on the west coast of the Big Island between Kawaihae and Kailua Kona. They sold the land 12 years later to a Japanese corporation. In Hilo, he bought a building in the Kanoelehua section of town for his office, having rented office space for 10 years.

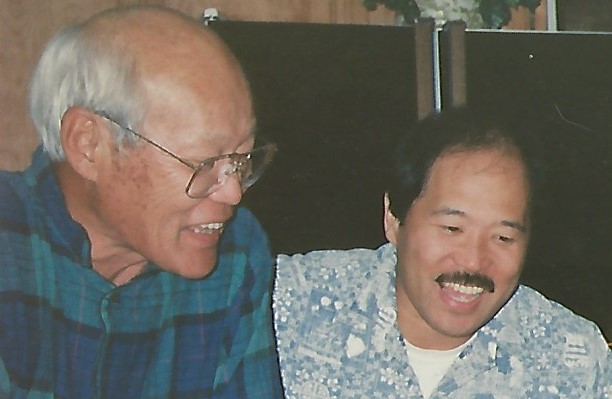

Tom Nakahara with his son Scott

Tom Nakahara was a member of Paauilo Hongwanji, Hamakua Lions Club, and American Legion Post 3. In 1962, he became a department commander for the American Legion, overseeing operations in Hawaii, Tokyo, Okinawa, and Guam.

Thomas Takashi Nakahara died on November 14, 2004, in Paauilo and was buried there. He was survived by his wife, two children, and eight grandchildren.

Researched and written by the Sons & Daughters of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in 2022, with assistance from Tom Nakahara’s son, who is a Lifetime Member.