442nd 71st Anniversary – 2014

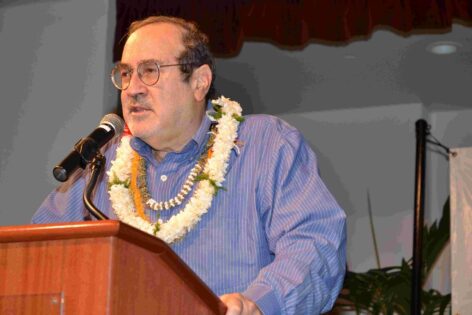

Honolulu, Hawaii – March 23, 2014. The 442nd Veterans Club held their 71st Anniversary Banquet in honor of the formation of their Unit. Over 600 veterans, family members and guests attended this memorable event, which was filled with lots of speeches and entertainment. Military historian and curator, Eric Saul delivered the keynote speech. Here is a copy of his inspiring speech:

Go For Broke: Japanese American Soldiers Fighting on Two Fronts

Speech for 442nd RCT 71st Anniversary Reunion

Honolulu, Hawai’i, March 23, 2014

By Eric Saul

“I think we all felt that we had an obligation to do the best we could and make a good record. So that when we came back we can come back with our heads high and say, ‘Look, we did as much as anybody else for this country and we proved our loyalty; and now we would like to take our place in the community just like anybody else and not as a segregated group of people.’ And I think it worked.”

– Nisei solder, Camp Shelby, Mississippi

“Hawaii is our home; the United States our country… We know but one loyalty and that is to the Stars and Stripes.”

– Nisei solder, volunteering for the U.S. Army

Who were you? First of all, you were Americans. You happened to be of Japanese ancestry. You were called Nisei. You were second generation, born in the United States. Most were born in the 1920s.

Where were you from? You were from Hawaii, Oahu, Maui, Kauai, Big Island. You were also from California, Oregon and Washington. You grew up in cities like Honolulu, Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, Sacramento, Fresno, and San Jose. You grew up in neighborhoods like Boyle Heights, the Palama District, and others. You lived in hundreds of small farming towns in the Western United States. You lived in the Little Tokyo’s and Japantown’s of the big cities on the West Coast. Here in Hawaii, you grew up on plantations with funny-sounding names like Hanapepe, Pu’unene and Lihue, where you toiled in the hot sun, helping your parents to harvest and process the sugar cane and pineapples.

You went to schools like McKinley, Garfield, and Roosevelt High School, named after great presidents.

You were raised to be Americans. As American as apple pie and hot dogs. You studied the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and American history. Every day, you pledged allegiance to the flag. You learned and were taught that you could aspire to anything that you dreamed. You were proud to call yourselves Americans. And you were proud to call yourselves Americans of Japanese Ancestry.

After school, you most often reluctantly attended Japanese language school. You resented having to sit in a classroom rather than playing baseball, football or basketball.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was a brutal blow. You were soon reminded that your faces were not like other Americans—you had the face of the enemy and all that it represented, but truly you had the heart of an American.

My friend, Nisei veteran Ted Tsukiyama, was serving proudly along with other Nisei in the Hawaiian Territorial Guard before Pearl Harbor. After the attack, you, Ted, and your Nisei comrades guarded the strategic areas around Honolulu.

Soon thereafter, you were assembled and told you could no longer serve. You were humiliated and embarrassed when your rifles were taken away from you.

You were mad as hell.

Instead of feeling sorry for yourselves, Ted, you and your Nisei comrades founded the famous Varsity Victory Volunteers. For months, you helped repair and build roads, helped construct buildings, and served the war effort, helping to prove the usefulness and the loyalty of the Nisei generation.

As a direct result, the local authorities here on Hawaii encouraged the Army to establish the all-Japanese American 100th Infantry Battalion, the One Puka Puka. Its proud regimental motto was “Remember Pearl Harbor!”

You were sent to Camp McCoy, Wisconsin. It was the first time most Hawaii boys had been off the island. In the winter, it was the first time you saw snow.

The Army watched while you trained, and you proved your patriotism, and showed that you were motivated to fight for your country.

As a result, the Army decided to create a full regiment of Japanese American soldiers. It was to be called the 442 Regimental Combat Team.

In Hawaii, they asked for 2,500 volunteers to join this fledgling unit. More than 10,000 of you Nisei raced to the recruiting offices. I remember hearing stories of those who were turned down and cried in disappointment.

We all remember those famous photographs of you standing in formation in front of the Iolani Palace, getting ready to march off to war. How proud were your mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, cousins and neighbors. How proud you were when you marched down King Street. When you went off to war, Hawaii and America would never be the same!

But, sadly, things were far different in California and on the West Coast. More than 50 years of racism against Asian Americans reared its ugly head after Pearl Harbor.

Soon, there were people of bad will calling for the removal and imprisonment of the Japanese community in Hawaii and on the mainland. Those groups included the fruit and vegetable growers’ associations in the Imperial Valley and the Central Valley in California. They were also chambers of commerce, city and state governments. They were civic and “patriotic” clubs like the Elks Club, the American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West, and many other organizations.

Many newspapers called into question your loyalty and wrote editorials calling for your removal from the West Coast.

In California and on the West Coast, you had few friends and advocates, and even less political power. Who would stand up to these ever-louder cries of “The Japanese Must Go!”

These voices of intolerance and bigotry were even heard in the halls of Congress. Who could have imagined that virtually the entire Congressional delegation of the West Coast could have overwhelmingly demanded your removal. The United States Army, and even the President of the United States, fell victim to the irrational and unjust cries for evacuation and internment of Japanese Americans from the West Coast.

The worst fears of the Japanese American community were realized on February 19, 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. It was enacted ostensibly to protect the West Coast. It was written under the false argument of “military necessity.” The order did not specifically name Japanese Americans, but all those who wrote it, justified it, and implemented it knew it was targeted against your mainland brothers and sisters.

Soon, 110,000 Americans, many who had lived in the country for more than 60 years, were forcibly removed from their lands and businesses and homes. There were scarcely more than a few days to prepare. The economic loss was in the tens of millions of dollars. The loss to the Constitution and to democracy was even greater. At a time when the laws protecting the rights of all citizens should have been the strongest, they buckled under the pressure of wartime hysteria, economic jealousy, greed, and expediency.

The wholesale removal of Americans from their property was a direct violation of every American tradition of law and justice.

America had turned its back on Japanese Americans. But Japanese Americans did not turn their back on their country.

So why would a young Nisei volunteer from a camp and leave his family after he had been deprived of virtually all of his rights? One Nisei told me that his family was sent from Los Angeles to the Santa Anita racetrack, which was an Assembly Center for Japanese Americans. There, they were put in a horse stall. Before the war, they had their own home in Los Angeles, and they were a middle-class family. Now they were living in a horse stall that had not been cleaned when they moved in, and it stunk of horse manure. His father said to him, “Remember that a lot of good things grow in horse manure, if you let them.”

442nd Chaplain Hiro Higuchi told me this story in 1980: “Sgt Masa Sakamoto was from Northern California. He was killed in Sospel. I was told to go up and get his body and bring it down. We had a little service in the cave there and it was my duty as the Chaplain to search his pockets in order to get everything home that can be sent home. I found a letter…all of his brothers were in the army in Japan…some vandals in California had burned down his father’s home and barn in the name of patriotism. And yet this young man had volunteered for every patrol that he could go on. You know, you can’t give a medal high enough for a man like that. We don’t realize how much these boys in California had to go through…to find a letter like that and his going out on a patrol and being killed.”

Eighteen thousand of you served in the 100/442/522.

Your regimental motto was “Go For Broke.” It was an old Hawaiian gambling term that meant “give it your all” or “shoot the works.” You truly lived up to that motto.

You fought in eight major campaigns in Italy and France: Naples-Foggia, Anzio, Rome-Arno, Southern France, the Rhineland, North Apennines, Central Europe and the Po Valley. You liberated numerous towns and villages throughout Europe, including the Italian port city of Leghorn, and the town of Bruyères, France.

You Nisei of the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team fought the toughest troops the Nazis could throw against you. They were battle-hardened troops from the Afrika Korps. SS troops, Panzer brigades, and soldiers from the Hermann Goering Division. You brave Nisei soldiers fought with the great divisions of the Fifth Army and the Seventh Army, including the 34th, 36th and 92nd Divisions. You fought courageously alongside the 10th Mountain Division and the 45th and 91st Divisions.

I see some of my many friends from various Companies of the 442nd here today. In one battle alone, the battle for the rescue of the Lost Battalion in October 1944, in which you fought, two thousand of you went in to rescue two hundred Texas soldiers who couldn’t be rescued by their own division. You went and suffered almost four hundred casualties in that one battle alone in almost five days of constant fighting. In K Company, you started off with 186 riflemen. By the time you reached the Lost Battalion, there were only 17 men standing. I Company fared worse. You started off with 185 men. By the time you reached the Lost Battalion, there were only eight men still standing in the company. It was unbelievable! You rescued the Texas Lost Battalion, and for that you earned two Presidential Unit Citations. The Army designated the rescue of the Lost Battalion to be among the top ten battles fought by the U.S. Army in its 239-year history.

Toward the end of the war, in Italy, in April 1945, General Mark Clark and the 5th US Army asked you to participate in an important campaign. They asked you to help break the German defensive line in Northern Italy, known as the Gothic Line. The US Army had three infantry divisions lined up to breach this major defensive position, which protected the Po Valley and the entrance to Austria. Those three divisions could not do it — they were stalemated for six months. The Fifth Army then asked the 100th/442nd, the “Go for Broke” Regiment, to break the stalemate. The officers and soldiers of the 100th/442nd said to the commander of the 92nd Division, “General Almond, we have a plan. We can create a diversionary attack and break the Gothic Line if you give us 24 hours.” General Almond said, “Impossible. We’ve had three divisions hammering away at the Gothic Line.” The Germans had their best SS Divisions on the mountains and it was considered an impenetrable fortress. He told the Niseis to “Just create a diversionary attack and we’ll do the rest.”

However, you Nisei soldiers had your own plan. You were smart. Your average age was about 21, and your average IQ was 116, which was eight points higher than necessary to be an officer in the army. You were barely 125 pounds soaking wet, but you were college-educated, and you were going to “Go for Broke.” So you climbed up that mountain called Mount Folgarita, which the Germans had so heavily fortified. You climbed it where they did not expect you. It was nearly a 3,000-foot vertical precipice. You climbed the mountain that could not be climbed in combat gear; the Germans could not possibly expect an attack from that point. From nighttime until dawn you climbed, almost eight hours. Men fell down as they climbed the mountain, and no man cried out as he fell, so as not to give away the position. At dawn you attacked—go for broke! You took the mountain and you broke the Gothic Line. It did not take 24 hours, as you thought, or a few weeks, as the Army had planned. It did not take six months. The U.S. Army reported that you broke the Gothic Line in only thirty-four minutes!

You Nisei soldiers earned more than 4,000 Purple Hearts during your service in Europe.

719 Nisei men made the ultimate sacrifice and were killed in action. The 100th/442nd suffered the highest combat casualty rate of any unit in World War II. There was a replacement rate of 314%.

You Nisei were awarded 18,143 individual decorations for bravery, including: 21 Congressional Medals of Honor, 52 Distinguished Service Crosses; 1 Distinguished Service Medal; 588 Silver Stars; 22 Legion of Merit medals; 19 Soldier’s Medals; 5,200 Bronze Stars and 14 Croix de Guerre, among many other decorations.

That record remains today. The 100/442 also received an unprecedented eight Presidential Unit Citations.

When you came home from the war, President Truman had a special White House ceremony for you. It was the only time that the President of the United States had a ceremony at the White House for a unit as small as a battalion. It was raining that morning in Washington, and Truman’s aide said, “Let’s cancel the ceremony.” Truman said to his aide, “After what those boys have been through, I can stand a little rain.” He said to the Niseis, bearing their regimental standard with the motto of “Go for Broke,” “I can’t tell you how much I appreciate the opportunity to tell you what you have done for this country. You fought not only the enemy, but you fought prejudice and you won. You have made the Constitution stand for what it really means: the welfare of all the people, all the time.” Lastly, he advised the Niseis to keep up that fight.

If the story of the 100th/442nd is unbelievable, there is a more unbelievable story. It is the story of the Military Intelligence and Language Service. More than 6,000 Niseis served throughout the Pacific in a super-secret branch of the military. Niseis provided the eyes and ears of intelligence and language skills that helped to break the stalemate in the Pacific. They broke secret codes, interrogated prisoners, provided valuable propaganda, and translated millions of documents to help win the war in the Pacific. By the war’s end, General Willoughby, General MacArthur’s chief of intelligence, declared that “the Nisei shortened the war by two years and saved a million Allied lives.” Never had so many owed so much to so few.

When the war ended in August of 1945, your work was not over, for now you served the peace. You were needed to bridge the language and cultural gap in the Allied Occupation of Japan. You did, performing again an indispensable role.

The U.S. occupation of Japan was one of the most benevolent and benign in world history. Japanese Americans helped write new laws and create new institutions. You helped in the institution of the modern Japanese constitution. You helped institute progressive land reforms and civil rights for Japanese women. One of the reasons Japan is the modern industrial giant that it is today is due to the role of you Japanese Americans in facilitating the transition from a military state to a democratic one. More than 5,000 Japanese Americans worked in Japan during the occupation, from 1945 to 1952.

For your contributions to winning the war and securing the peace, we owe you a debt of honor that we could never repay.

I, myself, had the honor to interview a number of you Nisei soldiers. In 1980, I was curator of the Presidio Museum and was creating a Nisei soldier exhibit called Go For Broke. I asked you, “Why did you volunteer for the Army?” Over and over again, you told me “It was so that my parents, my family, and my children could have a better life than I had.” You did it so that the racism that existed so prominently on Hawaii and the West Coast would be ended. You fought and sacrificed so that you would never have your loyalty questioned again.

You acted this way because you were taught concepts like giri and on, which mean “duty,” “honor,” and “responsibility.” You felt you had to pay back a debt to your country, even though that country did not offer you the opportunities it did to other Americans. Oyakoko: love for family. Your parents could not become citizens, but you loved your families and you knew you had to prove your loyalty at any cost. When you joined the Army, you were emissaries for your families to prove your love for democracy and justice when you volunteered from those degrading prison camps. Kodomo no tame ni: “for the sake of the children.” Enryo: humility. There’s an old Japanese proverb that says if you do something really good and you don’t talk about it, it must be really, really good. Gaman: internal fortitude, keep your troubles to yourself. Do not show how you are hurting. Shikata ga nai: sometimes things cannot be helped. Other times, you have to go for broke, and you can change things. Haji: do not bring shame on your family. When you go off to war, fight for your country, return if you can, but die if you must. Shinbo shite seiko suru: strength and success will grow out of adversity.

You Nisei not only helped win the war overseas, but you also helped win the war at home against prejudice, intolerance and misunderstanding.

Indeed, your children and all of us are the beneficiaries of this incredible wartime military history.

Because of the wartime service of you Nisei soldiers, the 500 laws in California and Hawaii that stood against Asians were struck down. You Nisei saw your parents become citizens in 1954. You saw your parents vote for the first time and actually own their own land. You saw your children succeed in business and the professions. You saw your comrade soldiers become legislators and political leaders, advancing the cause of civil rights for other minorities and groups in America.

You might say you Nisei were the greatest generation within the greatest generation.

When you Nisei came home from the war, you didn’t tell your wives, your families, or your children of your wartime experiences. The reasons were many. Because of the painful loss of your friends, the trauma of war, and because of your value of enryo—humility.

In 1988, after a long period of soul-searching, America apologized to the Japanese American community for its failures during the war. The very act that promulgated this reconciliation with democracy was named House Resolution 442, after the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

President Ronald Reagan, when he signed the bill enacting the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (HR442), remembered a speech that he had given right after the war, in California, at a memorial service for a young Nisei soldier, Kazuo Masuda. Masuda had been killed in Italy defending his buddies. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. In that speech, Reagan had said that “blood that has soaked into the sands of a beach is all of one color. America stands unique in the world, the only country not founded on race, but a way, an ideal.”

In 2000, twenty long-overdue Medals of Honor were awarded to Nisei in a ceremony at the White House.

One of the most remarkable legacies came after September 11, 2001. I remember watching the news when President George Bush, standing alongside his Secretary of Transportation, Norman Mineta, assuaged the fears of Arab Americans by saying that we were not going to repeat the mistakes of the past and that Arab Americans had nothing to fear from their country.

In 2011, the Congress of the United States awarded its highest honor, the Congressional Gold Medal, to you Nisei soldiers of World War II. I attended that ceremony and I recall how proud your children were, standing next to you, beneath the rotunda of our nation’s capitol.

As former Army Chief of Staff Eric Shinseki said, “We stand on the shoulders of giants.”

In the last few days here in Hawaii, I have had a chance to spend some time with your sons and daughters. I have heard things like:

“I am so proud of my father.”

“I know that I am living a better life because of what they did.”

“It makes me want to live up to their legacy.”

“I now really know how much we have because of their sacrifice. Until recently, I didn’t know how much they had been through. We must continue to preserve their memory and legacy forever.”

A few years ago, I remember speaking to one of my K Company friends, Tosh Okamoto, and he said to me, “You know, the awarding of the Medals of Honor to our boys is sort of the icing on the cake. I’ve sort of been angry for a long time at my country and what happened to us during the internment. Getting redress and the apology, and having the country recognize my buddies, lifted a cloud from my head. I now really feel like I’m truly American, and it was all worth it.”

Let us all remember and learn from these great men, the 33,000 Nisei who fought their precious war 71 years ago and won their place in history.

* * * * *