John Michio Nakamura

Private First Class

442nd Regimental Combat Team

3rd Battalion, K Company

John Michio Nakamura was born on January 16, 1921, in Flint, Michigan. He was the second son of William Noboru and Elsie Haru (Kuroki) Nakamura. His siblings were: Joseph F., Mary Hanako, Frank Toshun, Richard Yukio, and William H. (died in infancy).

William Noboru emigrated from Okayama Prefecture, Japan, arriving at Seattle, Washington, on January 10, 1907, on the Shinano Maru. The immigration card listed him as a “Machinist,” enroute to join Reverend Inoriyo at the Japanese Mission in Seattle. In 1910, he was living in a large boarding house with 28 other men who worked at a saw mill in Claquato Precinct, Lewis County, Washington. Haru emigrated in 1918. By 1920, they were living at 2108 Cumings Avenue in Flint, and William was working for the Chevrolet Motor Company as a Design Engineer. In 1930, William was a Drafting Engineer, and in 1940 he was a Mechanical Engineer at the auto factory.

John was educated in the Flint public schools. At Central High School, he was on the Student Council, the Arrow Head student newsletter, Press Club, Chemistry Club, and French Club. After graduating in 1938, he enrolled in Flint Junior College, where he worked on Clamor, the school newspaper. In February 1939, he led a roundtable discussion with several other area schools on “Selling Your Paper to the Students.” He then enrolled in the College of Literature, Science, and Arts at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

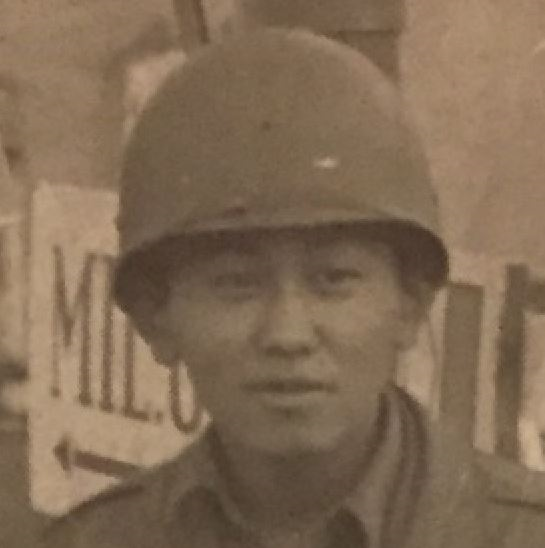

Right: John – Central High School Senior Class 1938

John was drafted into the Army in October 1941, and was assigned to the Signal Corps. Two months later, in December following the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt issued orders that declared Japanese living in the US were to be classified as 4-C/aliens (widely referred to as Enemy Aliens). John was honorably discharged from active duty “for erroneous induction” and classified 4-C. His father was fired from his position at Chevrolet, although they gave him work that he could do from home until he was reinstated eight months later.

“Johnny,” as Nakamura was known, was intensely patriotic and tried repeatedly to reenlist in the Army after his discharge. He even tried to enlist in the Military Intelligence Service – but was turned down as he could not speak Japanese.

On February 16, 1942, John registered for the draft at Local Board No. 5 in the Dryden Building in Flint. At the time, he was a student at the University of Michigan and living at 816 Tappan Avenue. His point of contact was his father William Nakamura of 2018 Cumings Avenue in Flint. John was 5’3½” tall and weighed 103 pounds. To increase his chances of being drafted, he visited his Senator and Congressman in Washington DC and asked for their assistance. In February 1943, after the Army announced that Nisei men could volunteer for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, Johnny was back in the service within a week.

He was assigned to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and sent to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, for training. He was assigned to 3rd Battalion, K Company, and was a “walkie-talkie” or communications man.

After months of training, the 442nd left Camp Shelby for Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia, on April 22, 1944. They shipped out to the Mediterranean Theater of Operations in a large convoy of troop ships on May 2 from nearby Hampton Roads and arrived at Naples, Italy, on May 28.

John participated in the Rome-Arno Campaign, entering combat on June 26 near Suvereto. After pushing the Germans north to the Arno River, the 442nd was sent to France in September to join in the Rhineland-Vosges Campaign. He was in the battles that liberated the towns of Bruyères, Belmont, and Biffontaine, and was in the battle for the rescue of the Lost Battalion.

John was with the Combat Team for the Rhineland-Maritime Alps Campaign from November 21, 1944, until they sailed from Marseilles to Italy on March 20-22, 1945.

In a letter home written from France in early 1945, John wrote:

Thank you for the birthday card. I can’t even begin to realize how time has passed. I don’t know if it has been a long time or a short time since January. Home seems neither near nor far away. It’s all something like a dream in which time is lost before it is even noticed to be passing. I said, ‘Why, yesterday was my birthday, and I didn’t even know it.’

You must not worry if I don’t settle down even after the war is over. I’ve learned much even being in the army. I’d stay in France two years before coming home if I could find a way of doing it – study French and literature and other things that interest me. Army life has made me feel free, even if I still haven’t chosen any profession yet. That doesn’t seem important as long as I can find a truly satisfactory life. When one is a child, his parents do all they can for him. When he grows up, he must do for himself.

The infantry is hard, it doesn’t make one any younger – 24 years and [I am] not yet settled. One must live some sort of life, and I could never be at ease if I hadn’t gone to take my share of this fighting. Everyone’s personal life is valuable to himself. He wants to be allowed to enjoy it. A man who hangs back and does not share Army service – if he is fitted for it and needed – actually is saying, “My life is more valuable to me. You can waste yours, but I shall keep mine.” That is wrong.

In March 1945, the 442nd was sent back to Italy for participation in the Po Valley Campaign. While there, he wrote the following in a letter to his family:

When I was in France, I used to think of Italy. I thought of that time we were thirsty and drank out of a stream. The next day, farther upstream, we found a couple of dead Jerries, a dead Italian lady who was pregnant, some dead goats and a dead cow. All of them had been in the water a long time. I also remember the 27 days from Grossetto to Pisa in which there was no rain or a single cloud. Now that I’m in Italy, all I can think about is Nice.

The mission of the 442nd RCT in the Po Valley Campaign was to conduct a surprise diversionary attack on the western anchor of the heretofore impregnable Gothic Line near Carrara before the full force of the Fifth Army was thrown against Bologna.

In a brilliant tactical execution, where the men had to get into position, hiking and climbing 3,000-foot Mt. Cerreta, Mt. Folgorito, Mt. Carchio, and Mt. Belvedere with their combat gear in the pitch-black night, the men of the RCT were successful in a surprise attack; breaking the formidable Gothic Line.

On April 5, 1945, as K Company was moving forward in support, Pfc John M. Nakamura was killed in action by the enemy firing a barrage of 80mm mortars and 75mm howitzers.

Sergeant Chester Tanaka of K Company later wrote to Johnny’s parents about a conversation with him the night before his death: John told me one night he expected to be killed the next day. I offered to take him out of the line for a few days, but John wouldn’t have it.

Less than a month later, the 442nd RCT went on from that breakthrough of the Gothic Line to see ultimate victory in Italy, when the Germany Army surrendered on May 2.

Private First Class John Michio Nakamura was interred at the U.S. Military Cemetery at Castelfiorentino, Italy, Section X, Row 32, Site 3281. He was survived by his parents; brothers Joseph F., Frank, and Richard Y., and sister, Mary.

For his military service, Private First Class John Michio Nakamura was awarded the Bronze Star Medal, Purple Heart Medal with one oak leaf cluster, Good Conduct Medal, American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with four bronze stars, World War II Victory Medal, and Combat Infantryman Badge. He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal on October 5, 2010, along with the other veterans of the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team. This is the highest Congressional Civilian Medal.

In 1948, the University of Michigan named a co-op dormitory in memory of John Nakamura.

Also in 1948, the remains of Americans buried overseas began slowly to return to the US if the family so wished. John was brought home on a U.S. Army troop ship and reinterred on December 2, 1948, at Arlington National Cemetery, Section 12, Site 4666.

For an article about John Nakamura written by a high school friend, see the following:

https://ezinearticles.com/?Bravest-of-Brave—World-War-II-Nisei-Hero&id=310011

Researched and written by the Sons & Daughters of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in 2021.