Kay Ryugo

First Sergeant

442nd Regimental Combat Team

171st Infantry Battalion, A Company

1st Battalion, A Company

Kay Ryugo was born on April 10, 1920, in Sacramento, California. He was the son of Jutaro and Mutsu (Naramura) Ryugo. He had one brother, Kikuji, and three sisters: Sumiye, Ida, and Minnie. Jutaro had arrived in Hawaii from Okayama Prefecture in 1897; then he went on to California in 1903. Mutsu arrived from Okayama Prefecture in 1910 in Tacoma, Washington. They were married on August 15, 1910, in Tacoma, upon Mutsu’s arrival.

In 1930, Kay was age 10 and living with his family at 518 S. Street, Sacramento, California. Father Jutaro was secretary of the Sacramento Growers Market, a wholesale produce company. In 1940, Kay was age 20, the family lived at the same address, and Jutaro now owned their home and a wholesale produce company.

Kay graduated in 1938 from Sacramento High School, where he was on the Class Council. He then attended Sacramento Junior College and earned an Associate of Arts degree in 194l. After college, Kay worked for his father at the company he had started, Associate Produce Company.

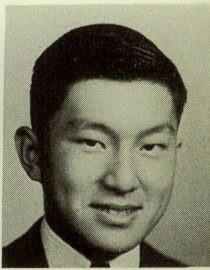

Right: Senior class photo

Kay signed his World War II Draft Registration card on July 1, 1941, at Local Board No. 25, Sacramento Court House. At the time, he was living with his family at 518 S. Street in Sacramento. His father was his employer at Associate Produce on 5th Street and 2nd Avenue, where Kay worked as a wholesale produce clerk.

The following recollections about his induction, training, and pre-442nd time in the Army are based on a post-war interview with Kay Ryugo.

On January 21, 1942, Kay Ryugo and other inductees left the Southern Pacific railroad station at 4th and I Streets in Sacramento about 10:00 p.m. They arrived at Camp Roberts (south of Salinas) in the morning and were immediately sworn in and given Army uniforms, fatigues, shoes, and toilet articles, followed by a physical examination and vaccinations. A dentist found that Kay had a cracked molar and he removed it, leaving a gap. He told Kay that they would give him a bridge after the war! The men were also given various tests, i.e., ability to differentiate different Morse Code phrases or sentences, number of stacked cubes, shapes of objects from flat drawings, and an intelligence test. The rankings of these tests were noted on Kay’s personnel record, which followed him wherever he was stationed.

A few days later, in January 1942, Kay and about 140 Nisei privates, including Jesse Miyao and Steve Sato from Perkins, and Harry Nakata from Kingsburg, were put aboard a train that headed east to Camp Robinson, in central Arkansas, for basic training. They were told to keep the window shades down at all times for safety (i.e., blackouts). At one stop, probably in southern Arkansas, they had to get up early for some exercise and to walk around the rail station. During a break, they went to the restroom at the end of the station. Some of the men went into the side labeled “Colored,” and got scolded by their officers who told them to go to the “White” side and never the other side.

Once the train arrived at the tent city at Camp Robinson, the new soldiers were separated into small groups and assigned to different companies as they were the first soldiers to arrive for basic training. Before any other new recruits arrived, the men were assigned to work in the kitchen and also to clean boxes of bolt-action Lee-Enfield rifles. Kay was in the same company as Harry Nakata and Tom Sakanari. Sakanari had been a boxer at the University of California at Berkeley. He later went to Officer Candidate School (OCS) and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant.

A few days later, new recruits arrived at Camp Robinson: a group arrived from the Chicago area, many with Polish names, while others of Native American extraction came from states west of Arkansas. The Nisei soldiers were issued blue fatigues, while the other recruits were issued olive drab fatigues. One recruit from Chicago said that he and others thought the Nisei soldiers were Japanese prisoners of war because of the blue color of their fatigues. Shortly thereafter, the Nisei soldiers were issued olive drab fatigues. Basic training lasted about ten weeks during which they “hiked, took marksmanship with their rifles, threw grenades, etc.”

After basic training ended, Kay and a large group of Nisei recruits were sent north by train to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, where they were attached to the Detached Enlisted Men Military List (DEML, also known as “damn easy military life”). They were given different work assignments at such facilities as the Officers Club, post theater, and post gymnasium. Kay worked as a clerk in the Special Services Section with Akira Hasegawa and two other soldiers. Hasegawa was a University of California at Berkeley graduate engineer. The Section had three officers: Major Robert Lough, former Superintendent of Schools in Idaho; and Captains Byron Yoder and Bernard Norsworthy. The captains were from Nebraska and belonged to the Aksarben Society (Nebraska spelled backward). Their Special Services office was responsible for the athletic equipment used in the field house, the Army Relief Fund, management of the guest house, and other services. On one occasion, Kay traveled with Major Lough to a home in rural southern Missouri to see a mother with a sick child; the father was absent as he was in the Army. After seeing the sick child, Major Lough ordered Ryugo to write the mother a check for $50 from the Army Relief Fund, so that the child could be seen by a hospital physician.

Others in Kay’s detachment worked in the Officers Club as bartenders and operated the cameras in the post movie theaters.

It was clear that these men stayed in touch over the years and their families knew each other well. In his post-war interview, Kay recalled members of the DEML detachment who became lifelong friends: George Fujita, Ken Hirose, George Masuda, Art Shimizu, and Tom Takata. Years later, Kay attended George Fujita’s funeral in Sacramento. Jessie Miyao gave the eulogy. George Fujita had married Mirry Miyake, who was the daughter of a good friend of Kay’s mother-in-law. The Fujita’s daughter had married Jessie Miyao’s son. And Fujita’s sister had married the brother of another DEML man, Art Shimizu.

In early May 1942, while Kay was still at Fort Leonard Wood, his family was forcibly sent along with other Japanese Americans to the Sacramento WCCA Assembly Center, followed on June 24 by incarceration at Tule Lake WRA Relocation Camp in far northern California. As it turned out, a female friend from childhood and college, named Masako Miyake was also incarcerated at Tule Lake. Masako was released to St. Cloud, Minnesota, on January 13, 1943. She and Kay would marry that year. The Ryugo family was released on various dates in 1942 and 1943 to St. Louis, Missouri, and Cleveland, Ohio.

In 1943, Kay and some of his group, including Art Shimizu and cousin Ben Kumagai, were sent to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, as cadre for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Other Nisei also came from different camps and forts to serve as cadre. They were housed in a 10-man hutment for each squad; three squads per platoon; and three platoons per company, plus a first sergeant, supply sergeant, armor artificer, truck driver, Sgt. Ono in charge of the mess, plus two cooks (George Kihara, and Harry Tamura of Hood River). Kay was the company clerk for A Company, 1st Battalion.

In April of 1943, a group of men from the cadre, including Ken Hirose, Tom Momii, Lou Miyamoto, Harry Nakata, and Art Shimizu, were given 3-day passes and furloughs. They could not enter the 9th Corps Area (California, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington, which were off-limits to Japanese, whether they were a citizen or a soldier). Kay visited Amache Relocation Center in Colorado and stayed with the Tanita family, whom he had known back in California when they were prune farmers in Napa and he was attending Sacramento Junior College.

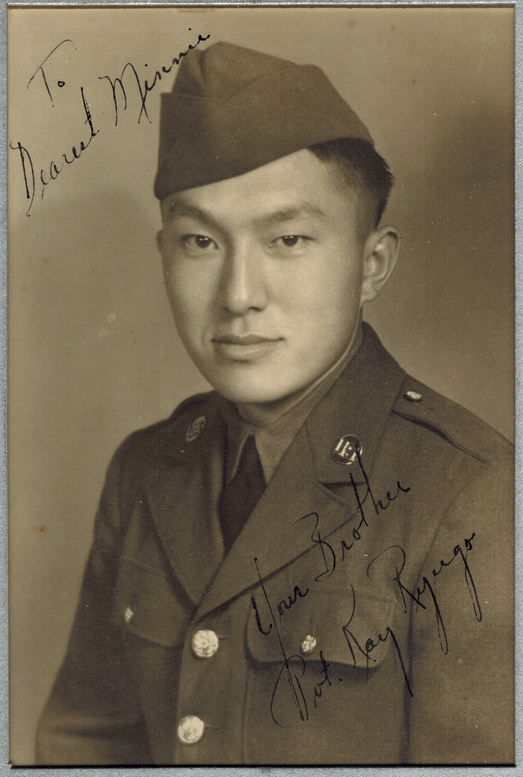

Right: Army photo in original frame

On April 13, 1943, the Hawaiian contingent of 2,686 new soldiers arrived at Camp Shelby to serve as a nucleus of the 442nd Infantry Regiment. As more units were added, the Regiment was named the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Some friends from back home arrived and were assigned to the 442nd’s Cannon Company: Yoshio (“Yoho”) John Kashiki, Arthur (“Art”) Nobuo Doi, and Shuki Hayashi.

Basic training lasted from May 10 to August 23. In late summer of 1943, Kay and some 442nd soldiers were sent to Dothan, Alabama, to guard 500 German prisoners who were sent there to harvest peanuts. The POWs put unearthed peanut vines into stacks to dry. Some of the POWs were anxious to learn what cities were being bombed by the Allies, but Kay could not speak German and was unable to answer them.

In the fall of 1943, Kay got a pass and traveled to St. Cloud, Minnesota, to visit Masako. She had written to him earlier and he had answered, so she was expecting him. They went for a walk along the Mississippi River where he proposed to her. As he later recalled, “She responded with a ‘yes’ and twinkling, teary eyes.” He spent the night in St. Cloud and returned to Camp Shelby via Chicago, Memphis, and Jackson, Mississippi. In early September, he was promoted to Sergeant.

In early 1944, many men from 1st Battalion had been sent as replacements to the 100th Infantry Battalion already fighting in Italy. Other men from 1st Battalion were transferred to other battalions of the 442nd, making them overmanned.

During this time, Kay Ryugo was promoted to Staff Sergeant and platoon leader.

In early April of 1944, Kay got a pass and went to St. Louis where his parents, his sister Sumiye, and her husband Robert Ashizawa had been living since their release from Tule Lake WRA Center in September. Masako was also there and she and Kay were married at the Ashizawa’s home on April 14, 1944. Masako then moved to Hattiesburg, where Camp Shelby was located. She was active there in the local Fifth Avenue Baptist Church. Over the years, they raised a family of three sons and two daughters.

On April 22, 1944, after going through basic and advanced training, and maneuvers in DeSoto National Forest, the 442nd RCT, without its 1st Battalion, left Camp Shelby for Virginia. And on May 2 they left from Hampton Roads for Italy.

The 1st Battalion, including Sgt. Kay Ryugo, was left at Camp Shelby. It was renamed the 171st Infantry Battalion and their job was to train Nisei recruits that were arriving from all over the country, including from the WRA Relocation Centers. The 171st officers were all Caucasians. Captain Robert S. Blake from San Carlos, California, was commander of A Company. Kay later recalled that Capt. Blake often did not appear for reveille, so Kay forged Blake’s name on the Morning Report. The other officers refused to sign it, perhaps thinking that Captain Blake would be reprimanded for his tardiness.

When Ken Hirose left for OCS, Kay Ryugo was promoted to First Sergeant of A Company.

In the spring of 1945, the 171st Infantry Battalion was disbanded and its men were sent to Fort George G. Meade, Maryland, the port of embarkation for Europe. Soon after they arrived, however, Germany surrendered on May 8. Kay and several other Nisei soldiers were sent to Camp Ritchie, Maryland, which he had heard was a center for counter-intelligence. At Camp Ritchie, a Nisei captain interviewed Sgt. Kay Ryugo about his views on the war, asking if he had any relatives in the Japanese army or navy. Sgt. Ryugo replied that an uncle was an Imperial Army officer and his cousins were probably in the Imperial Navy. He was asked if he would shoot his uncle if he met him on the battlefront. Kay responded that, “I would not let a Japanese soldier get close enough to ask any questions; I’d shoot first.” He thought he had failed the test as he was soon sent to Camp Bullis, Texas, to a Military Police detachment, presumably to interrogate prisoners of war. But the men sent there were not given Japanese language lessons. While there, Kay learned to shoot different firearms, including a Thompson machine gun. In the meantime, on September 2 the Japanese signed the surrender to the United States on the USS Battleship Missouri. While at Camp Bullis, a comrade of Kay’s named Tei Yamaguchi and others were sent to Japan as part of the occupation troops, while Kay stayed to guard the perimeter of the game refuge against poachers.

Kay recalled an incident during this time at Camp Bullis. One day, he and his jeep driver stopped at an outpost guarded by a sergeant who was on horseback. When they asked if they could ride the sergeant’s horses, he gave permission, so Kay and his driver got on and started out on the gravel road. After a short period, they turned the horses around, and to their surprise the horses promptly galloped all the way back to the stable, running close to trees and low-hanging limbs. Even though Kay pulled on the reins, his horse would not slow down, but just kept on galloping as fast as he could. When they arrived at the stable, the sergeant scolded them for making the horses run so fast and getting sweaty. Kay told him that he was also sweaty and the horses wanted to throw them! Kay recalled that he was unable stand up for a few days because “my thigh muscles and rump ached so much.”

In December of 1945, Kay was sent to Fort Sam Houston, in San Antonio, Texas, to be discharged from the U.S. Army after 47 months of service. He later wrote that while he was getting his separation papers, a man approached him and said, “I know you; you were with me in Camp Robinson.” The man was Corporal Bracale, who had been his trainer at Camp Robinson. Bracale had been sent to the South Pacific where he was wounded in action. Kay marveled at what a small world it was.

For his military service to his country, Sergeant Kay Ryugo was awarded the Army Good Conduct Medal, American Campaign Medal, and World War II Victory Medal.

After getting his discharge papers, Kay was issued a new uniform and money to return to Sacramento where he had been inducted. However, he went instead to St. Louis where Masako was living with his parents. In St. Louis, Kay found work at a rag factory, directing bales of material from different sewing factories to be sorted by different workers. After a few months, he quit this job and went to work for his brother-in-law, Robert Ashizawa, who had opened a dry cleaner in west St. Louis. After a few months, Kay decided to continue his college education and applied to various institutions.

Kay was accepted by the University of California at Davis, so he and Masako traveled back to Sacramento. They stayed at the home of Mr. Itano on 4th Street,, with Mas and Ida Yamaguchi (his sister and her husband). Kay and Masako commuted to nearby Davis for a couple of semesters before renting an apartment in the school’s “Aggie Villa,” which was used as housing for returning veterans.

Left: Masako and Kay

Kay was a Horticulture major and graduated with a Bachelor of Science in 1949, and a Master’s degree in 1950. He went on to earn his Ph.D. at Davis in 1954 in Plant Physiology. He was appointed an Agricultural Experiment Station Assistant Researcher in the UC Davis Department of Pomology. After several advancements, in 1978 he was awarded the title of Professor and Pomologist in the Agricultural Experiment Station. His research was broadly focused on the changes in the tissues of commercially important deciduous fruit trees cultivated in California. He retired in 1988 after 34 years of service to the University.

Kay was also skilled at ceramics and woodworking and he made numerous pieces of art, furniture, and musical instruments, particularly violins.

Masako died on December 14, 2008, in Sacramento. Kay Ryugo died in Boise, Idaho, on June 13, 2016. Kay and Masako left a family of five children, six grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

Friends and colleagues remembered Kay as an outstanding neighbor and citizen, “an amazing guy,” and a “man of great dignity and wisdom.”

Kay and Masako are buried in Davis Cemetery at Birch Lane in Davis, California.

Researched and written by the Sons & Daughters of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in September 2021, with information from the Ryugo family.