Soldier Story: Charles Matsuo Igarashi

Soldier Story

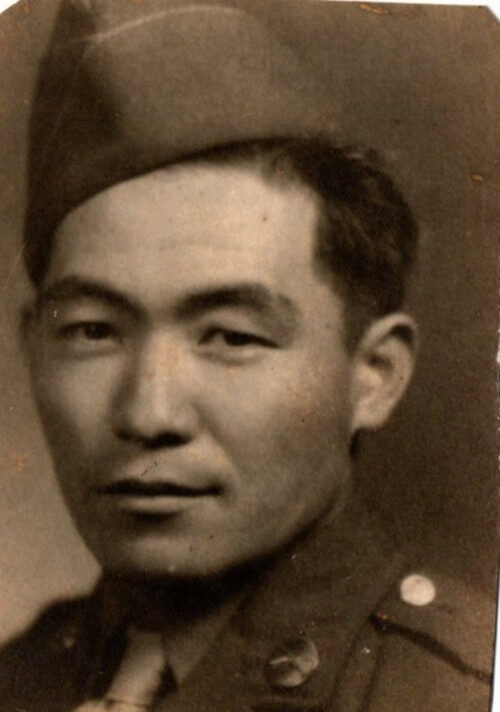

Charles Matsuo Igarashi

Private First Class

442nd Regimental Combat Team

3rd Battalion, K Company

Matsuo Igarashi was born on January 26, 1915, in Waialua, Oahu, Territory of Hawaii. He was the eldest child of Fujimatsu and Haru (Nagai) Igarashi. They arrived in Hawaii from Japan in 1899 and 1912, respectively. Haru arrived at the age of 19 as Fujimatsu’s wife on September 3, 1912, on the Nippon Maru, from the village of Seiro, Niigata Prefecture, Japan. She was born in the village of Miyoshi, Niigata Prefecture. At the time, Fujimatsu was living in the sugar plantation area of Aiea, Oahu. There were five children born to Fujimatsu and Haru: sons Matsuo, Haruo, and Masato, and daughters Mitsue and Fujiko.

In 1920, the family was living in Waialua where both parents worked at the Waialua Sugar Mill. In 1930, they were still in Waialua, and only father Fujimatsu was working at the mill. Matsuo graduated from Andrew E. Cox Junior High School on June 10 that year. After one year at Waialua High School, he dropped out and began working at the Waialua Sugar Mill. He also joined the Waialua Young Mens’ Association. In October 1938, he was on the program committee for the YMA’s community picnic at Puuiki Beach – an annual event attended by over 1,000 people, nearly the entire Japanese population of Waialua. In 1940, Matsuo was living with his family in House #20, Mill Camp No. 9, and employed as an oiler in the engine room at the mill. His father was a mill worker and his mother was working on the sugar plantation.

Matsuo Igarashi signed his draft registration card on October 26, 1940, Local Board No. 11, at the Waialua Fire Station. He lived with his family and their address was P.O. Box 243, Waialua. Sister Mitsue was his point of contact. He was employed by Waialua Agricultural Company, Ltd. Igarashi was 5’3-1/2” tall and weighed 118 pounds.

In 1942, Matsuo and his father Fujimatsu were among the Mill Camp No. 9 donors to the Waialua Plantation Victory Unit that raised $2,805.29 in two weeks for the Red Cross. The Victory Unit was organized by Waialua Plantation workers of Japanese ancestry to raise funds for worthy wartime causes.

Igarashi enlisted, using the name Charles Matsuo, on March 23, 1943, in the U.S. Army. His civilian occupation was given as “Semi-skilled welder and flamecutter.” He was sent to the “tent city” known as Boom Town with the other new soldiers at Schofield Barracks. On March 28, he was present at the community farewell ceremony for the 442nd at Iolani Palace. He left on the S.S. Lurline on April 4 with the 442nd. From Oakland, California, they travelled by train across the US to Camp Shelby, Mississippi.

Igarashi was assigned to K Company. After a year of basic, combat, and specialized training and field maneuvers, the 442nd left Camp Shelby on April 22, 1944. They travelled by train to Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia. On May 2, they sailed from nearby Hampton Roads in a convoy of about 100 ships, arriving at Naples, Italy, on May 28.

After a week in bivouac at nearby Bagnoli, the 442nd was sent by LSTs to Anzio, and then they were trucked through the recently liberated city of Rome to a large bivouac area at Civitavecchia. There, they prepared for movement to the front lines. This was the Rome-Arno Campaign.

Igarashi fought in this campaign, entering combat with the 442nd near Suvereto on June 26. The RCT pushed the enemy steadily up the Italian peninsula, liberating towns as they moved north. Their mission was to take the port town of Livorno, and it became clear that the enemy was abandoning the port and moving north to their defenses on the Arno River. Igarashi’s K Company made a frontal attack on Luciana, the hilltop town northeast of Livorno, and gained a toehold by nightfall. Finally, late on July 17, K Company had cleared out the last resistance in the town.

On July 18, Livorno fell to the Allies, and Igarashi’s 3rd Battalion along with the 2nd Battalion continued to push north, meeting only scattered resistance. They took Colle Salvetti, which was on the last high ground south of the Arno River. The Germans were still defending the area just south of the Arno, but not heavily. On July 21, the 442nd pushed out as far as the main east-west road, Highway 67, between Livorno and Florence, set up defensive positions there, and moved an outpost line some distance beyond the highway itself.

That night, all elements of the RCT were relieved from the lines and pulled back to a bivouac near Colle Salvetti. After three weeks of combat, the 442nd was below effective combat strength and needed to await replacement troops.

On July 22, most of the 442nd, including Igarashi’s 3rd Battalion, was moved from Colle Salvetti to an Allied rest area around Vada, about 20 miles south on the Ligurian coast. They remained there until August 20. During this time, they rested, and from August 1 on they resumed training, including extensive maneuvers, training in mountain fighting, and working on and ironing out problems that arose in combat situations.

When they left Vada in late August, Igarashi’s 3rd Battalion and the 2nd Battalion moved back into the lines on a 6-mile front on either side of the Greve River juncture flowing north into the Arno. They ran patrols constantly – the ground was level but so heavily crisscrossed with hedges and vineyards that visibility was usually under 100 yards. The goal of the patrols was to capture prisoners who would hopefully give valuable information about what the enemy knew of our plans or their own plans and troop dispositions. There was also much harassing artillery fire from the enemy that resulted in ongoing casualties for the 442nd.

On September 1, Companies K and F crossed the Arno and established a bridgehead perimeter to guard the crossing from enemy attack. At this time, the 7th Army wanted the 442nd for the battles in France, and the 5th Army wanted to keep the Nisei for the battles for the Gothic Line in Italy. Igarashi’s K Company remained in position on the bridgehead until September 5, when the final decision was made for the 442nd to join the battles in France.

The next day, the 442nd was detached from the 88th Division and moved south, prior to being transported to Naples and shipment later in the month to its next assignment – the Rhineland-Vosges Campaign in France.

In France, the 442nd engaged in their most bitter fighting yet. They were transported 500 miles north from their arrival in Marseilles to the Vosges Mountains of northeast France, close to the German border. After liberating the important rail and road town of Bruyères and the nearby villages of Belmont and Biffontaine, they were given a brief rest in Belmont before suddenly being ordered back to the front lines. Their mission was to rescue the 1st Battalion of the 141st (“Texas”) Regiment that had become nearly encircled behind enemy lines. Attempts by other units of the 141st had failed in the rescue. On October 30, the Texans were rescued and the 442nd continued pushing the Germans through the mountains.

Finally, on November 17, the 442nd was relieved from the front lines after 25 days of heavy fighting. At the time, they were under-strength due to high casualties. As a result, the Combat Team was sent to southern France to rebuild to full combat strength while fighting in the Rhineland-Maritime Alps Campaign. This was mostly a defensive position guarding the French-Italian border from attack by the German Army in Italy.

On arrival in the south, Igarashi and the 3rd Battalion relieved the 19th Armored Infantry Battalion in the small border town of Sospel on November 23. From there, the men headed for the higher mountains. Where there were border forts on the peaks, they rode in trucks. Otherwise, they climbed the 4,000’ peaks with their pack mules and equipment. Combat and reconnaissance patrols roamed back and forth between the lines, sometimes making enemy contact. There were a lot of mines in the area and no knowledge of where they were. Thus, many 442nd men were wounded by U.S. mines. Often, the Germans fired artillery at the 442nd as a reminder of their presence.

On December 21, 3rd Battalion was in the area of Sospel and was relieved by 2nd Battalion. They moved to the nearby village of L’Escarène as regimental reserve. The 3rd Battalion companies got together and hosted a Christmas party for the children of the village. During the rest of the 442nd’s time in southern France, the pattern of alternating duty in the Sospel area continued. The men were often given one-day passes to enjoy leisure time in Nice. For this reason, the Rhineland-Maritime Alps was nicknamed the “Champagne Campaign.”

The 442nd was in southern France from November 23, 1944, until March 15, 1945, when they were relieved and moved in relays to a staging area at Marseille. On March 20-22, the 442nd (without its 522nd Field Artillery Battalion who were sent to Germany) left France to fight in the Po Valley Campaign for the final push to defeat the Nazis in Italy. They arrived at the Peninsular Base Section in Pisa on March 25 and were assigned to Fifth Army.

The objective of the 442nd was to execute a surprise diversionary attack on the western anchor of the German Gothic Line. This elaborate system of fortifications had been attacked in the fall of 1944, but no one had yet been able to pry the Germans loose from the western end. The Gothic Line in this area was hewn out of solid rock, reinforced with concrete, and constructed to give all-around protection and observation. The Germans were dug into mountain peaks rising almost sheer from the coastal plain, bare of vegetation save for scanty scrub growth.

The Combat Team left their initial staging area in Pisa and moved to a bivouac at San Martino, just north of the walled city of Lucca. While there, all units used their time for training. Firing ranges were set up and the men spent hours adjusting their newly issued weapons to the highest accuracy. New replacements who had no combat experience practiced small-unit problems with their squads and platoons day and night.

Starting on April 3, the 442nd conducted a surprise attack on the Germans at Mount Folgorito. From that point on, the Combat Team continued pushing the enemy north, with fierce fighting but continued success.

As 3rd Battalion probed Mount Nebbione from all possible angles, 2nd Battalion tried a wide encirclement from the south. All of these were beaten back. By this time, the 442nd had been climbing up and down 3,000’ peaks for two weeks with little rest. And the regiment was somewhat scattered by its various attempts to flank the enemy forces. On April 20, the 442nd battalions regrouped in the vicinity of Marciaso and prepared to attack north. The mission was to cut off two major highways and strike at Aulla. The 3rd Battalion remained to continue the attack on Mount Nebbione, the last German defense just south of Aulla.

K Company struck at the ridge between Posterla and Tendola to the north. On April 22, K Company hit Tendola with all three platoons, two from the north and one from the south. The firefight lasted all day and into the night. The next day, Mount Nebbione fell.

After these battles, the 442nd moved farther north, finally taking Aulla on April 25, penetrating as far north as Torino. The 442nd relentlessly pursued their diversionary attack, resulting in a complete breakthrough of the Gothic Line in the west. Despite orders from Hitler to fight on, the German forces in Italy surrendered on May 2, 1945, a week before the rest of the German forces in Europe surrendered.

Igarashi was with the 442nd while in occupation at Ghedi Airfield guarding and processing German prisoners, the move to Lecco, and the return to the Livorno/Pisa/Florence area on July 12 for further guard duty.

After serving during the occupation for several months, Charles returned to the US and was discharged from the Army on November 7, 1945.

For his World War II service, Pfc. Charles Matsuo Igarashi was awarded the following decorations: Bronze Star Medal, Good Conduct Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with four bronze stars, World War II Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal, Distinguished Unit Badge, and Combat Infantryman Badge. He was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal on October 5, 2010, along with the other veterans of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. This is the highest Congressional Civilian Medal.

Igarashi returned to the family home at Mill Camp No. 9. He married Kimiyo Niimi of Puna, Hawaii island. Over the years they had one daughter, Shirley Kiyoko. In 1950, they were living with his mother in Mill Camp No. 8, in Waialua. Igarashi worked for the U.S. Army as a diesel and automobile mechanic in the motor pool.

Charles played in the Waialua Golf Club and participated in tournaments around Oahu. He was an active member of the Rural Chapter of the 442nd Veterans Club, serving as Vice President in 1955 and President in 1958. The Rural Chapter was for veterans who lived in the Wahiawa and Waialua areas. He was also a founding member of their fishing club.

Charles M. Igarashi died at his residence on January 28, 1997, two days after his 82nd birthday. He was survived by his wife Kimiyo, daughter Shirley, brother Haruo, and sisters Mitsue Suzuki and Alice Masatsugu. He was buried in Mililani Memorial Park, Section E. Kimiyo died on June 8, 2008, and was buried next to her husband. They were members of the Waialua Hongwanji Mission.

Right: Shirley Igarashi with her father’s photo, 2023 Annual 442nd Banquet, Fort Shafter

Daughter Shirley Igarashi was a valued and faithful member of the Sons & Daughters of the 442nd, serving as Treasurer for many years. She passed away on April 3, 2023, and was buried next to her parents. Shirley donated her father’s military medals to the 442nd Veterans Club, where her father had been a member and where she had also worked for several years as its Secretary.

Researched and written by the Sons & Daughters of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in 2025.