Soldier Story: Halo Takashi Hirose

Soldier Story

Takashi Halo Hirose

Private First Class

D Company

100th Infantry Battalion

442nd Regimental Combat Team

Takashi Hirose was born on September 23, 1922, in Puunene, Maui, Territory of Hawaii. He was the son of Denkichi and Shina (Miyoshi) Hirose. His siblings were: brother Tatsuo, and sisters Evelyn Sadayo, Harriet Hideyo, and Yaeno. Denkichi and Shina arrived as a married couple on June 28, 1903, from Masuda-cho, Shimane Prefecture, Japan, on the S.S. City of Peking. Shina was Denkichi’s second wife. They were initially contracted to work at Ewa Plantation on Oahu. But they did not care for the luna (plantation overseer), so they went to live at the Young Hee Camp (Camp 5) at the Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar (HCS) plantation in Puunene, where Denkichi worked. They remained there the rest of their lives. When Denkichi signed his World War I draft card on October 26, 1918, he was employed as a surveyor for HCS.

In 1930, father Denkichi was a laborer on the plantation and eldest son Tatsuo was a carpenter for the county government. In 1940, Denkichi was a watchman, and Tatsuo was a foreman. In addition to Takashi and the three daughters, also living in the household were Tatsuo’s wife Chiyoko, daughter Yuriko, and sons Masami and Masaharu.

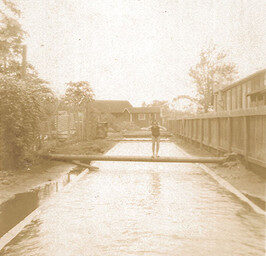

Left: Takashi, 1927 over a Puunene irrigation ditch

Takashi learned to swim at a very early age in the sugar plantation irrigation ditches of Puunene. He was given the nickname “Halo” when another boy berated his failure to catch a pop ball during a sandlot ball game, calling him “hollow.” Takashi did not like the name, but it stuck nonetheless, and he eventually got used it and kept the name into adulthood.

Watching over the young kids swimming in the irrigation ditches was Soichi Sakamoto, a science teacher at Puunene school. At first, Sakamoto knew nothing about swimming, but in time, he became a swimming coach for his “ditch kids.” Halo later recalled: “We just swam and had fun until Coach came along. Then it was hard work every day.” He played barefoot football and basketball. In 1937, Sakamoto started the Three-Year Swim Club (3YSC) and Halo was one of his stars. One of the coach’s methods was to have his members develop strength and resistance by swimming against the rapidly moving current in the irrigation ditches.

Sakamoto had begun the 3YSC to train his swimmers to qualify for the US team at the 1940 Olympic Games in Tokyo. Their motto was, “Olympics First, Olympics Always.” Halo competed at the 1938 Hawaiian AAU Outdoor Championship at the Honolulu War Memorial Natatorium on June 9-10.

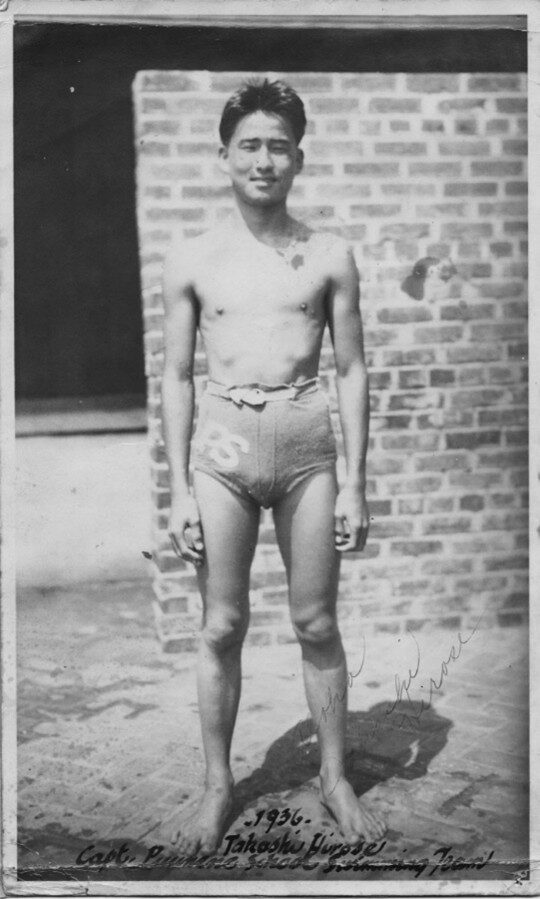

Right: 1936, Halo was Captain of the Puunene School Swim Team

He was named a member of the 1938 All-American Swim Team, competing in late July at the U.S. Nationals in Louisville, Kentucky, where he placed second in the 200-meter freestyle, finishing just inches behind the winner, Adolph Kiefer, 1936 Olympic champion. His expenses from California (where he competed with a group of Hawaiian All-Stars) to Kentucky were paid for by the people of Maui.

Halo earned a spot on the US team that toured Europe from June to September 1938 and the distinction of being the first American of Japanese ancestry (AJA) to represent the US in international competition. They competed in two big meets – in Berlin and Budapest. In Germany, Halo was part of the 4x100-meter freestyle relay team that set a new world record.

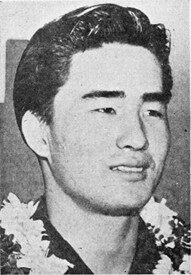

Left: September 1938 upon returning on the S.S. Matsonia from Germany, age 16, “a bit bewildered and modest as ever”(two photos)

At the end of 1938, Hirose was notified that he was appointed to the All-American Swim Team in the category of 800-meter freestyle relay. He received an All-American certificate, and official sweater and swim trunks, bearing the red, white, and blue shield of the All-American Swimming Board, the highest swimming authority in the U.S.

In 1939, Halo competed in the National AAU Outdoor competition in Detroit, Michigan. He was then selected by the U.S. Olympic Committee to be on the team, coached by Mike Peppe, that represented the US in Guayaquil, Ecuador, that summer at a swim meet to mark the dedication of a new swimming pool. This was the forerunner of the Pan American Games. Halo next competed as part of the Hawaii team at the National AAU Outdoor competition in Santa Barbara, California.

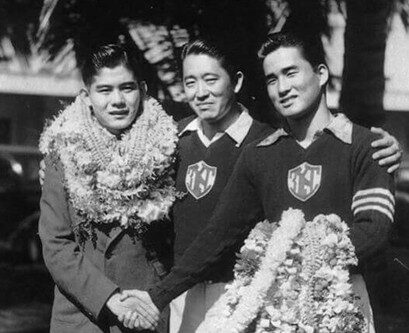

Right: Welcoming Keo Nakama back home from Australia, April 12, 1939 – Coach Sakamoto and Halo Hirose wearing their new 3YSC sweaters.

Halo was in training for the U.S. team at the 1940 Olympics in Japan; however, it was announced that the Games were cancelled. That year, he smashed, by .3 seconds, Johnny Weissmuller’s record in the 100-yard freestyle at the Punahou School pool during the Hawaiian AAU Indoor Championship meet. At an exhibition for the meet, he and teammates Keo Nakama, Bunmei Nakama, and Jose Balmores swam the 800-meter relay and smashed Yale University’s recognized world record by 13.1 seconds.

After graduating from Maui High School in 1940, Halo moved to Honolulu where he entered the University of Hawaii (UH) on a scholarship with the intent of a major in Physical Education. After his sophomore year, however, he dropped out of UH and found employment with the Honolulu Fire Department, working at the Moiliili Fire Station. During this time, he continued competing in swimming meets for Hawaii. In 1941, at the U.S. National AAU Championship he won the 100-meter freestyle and was on the first-place 800-meter freestyle relay team.

Hirose registered for the draft on June 30, 1942, Local Board No. 3, Room 211, National Guard Armory, in Honolulu. He was 5’7” tall and weighed 155 pounds. His address was 2535 South King Street. His point of contact was a friend, Melvin Abreu of 846 10th Avenue. Throughout 1942 and early 1943, he continued to swim in competitions and exhibitions.

Hirose enlisted in the U.S. Army on March 24, 1943. His enlistment form stated that he had completed two years of college. He was sent to the tent camp known as “Boom Town” at Schofield Barracks where he was an “Acting Sergeant.” After the aloha farewell ceremony given to the new soldiers by the community at Iolani Palace on March 28, they left Hawaii on the S.S. Lurline on April 4 for California. Upon arrival in Oakland, the soldiers were sent by train to Camp Shelby, Mississippi.

Halo was assigned to M Company, the heavy weapons company of 3rd Battalion. As soon as basic training ended on August 23, he headed to New Orleans, Louisiana, where on August 24-25 he captained a squad of 442nd swimmers who competed in the Southern AAU Senior Swimming and Open Championships. The team scored 53 points to its nearest rival’s 17 and they won a total of 16 medals. The entire expenses for their trip to New Orleans was paid for by Earl Finch, the Hattiesburg rancher who would come to be known as the “godfather” of the 442nd. Before the meet, he paid for them to train at Hattiesburg’s Southern Methodist University pool. After the meet, Finch treated them to dinner at the fancy Roosevelt Hotel. Although the men were out of shape swim-wise, they still dominated.

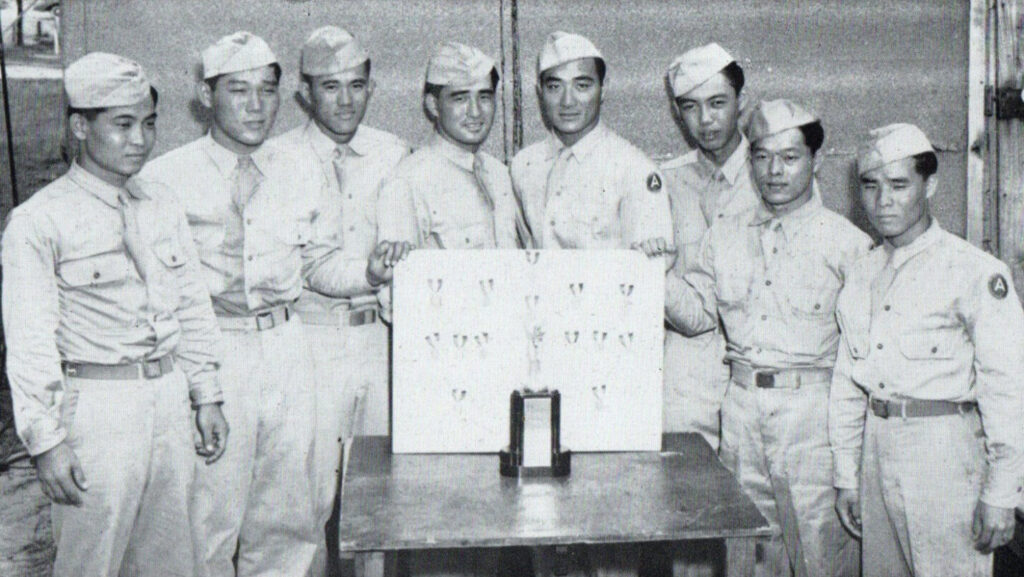

Below: 442nd Swimming Team at Camp Shelby, 1943, with their medals, L to R – Mike Mizuki, John Tsukano, Charles Oda, Halo Hirose, Francis Tanaka, Joe Yasuda, Tom Tanaka, Robert Iwamoto

Back at Camp Shelby, unit training and field exercises occupied the men. Then in January 1944 the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate), mostly Hawaii soldiers who were already fighting in Italy, called upon the 442nd to furnish replacement troops, needed due to high casualties. Many men volunteered to go, and others were assigned. According to Halo, he and some of his Puunene friends thought it would be the “fun thing to do,” and they volunteered. As he said later, “We never thought about what we were getting into.”

Private Hirose was among the first group of replacements sent to Fort George G. Meade, Maryland – 10 officers and 165 EMs (enlisted men). They left for Europe on February 22 and arrived in Oran, Algeria. After some time there, they finally arrived to the 100th Battalion at a rest camp at San Giorgio, near Benevento, Italy, where Halo was assigned to a machine-gun platoon in D Company. On March 24 the 100th left Naples (about 50 miles away from Benevento) and boarded LSTs for the Anzio beachhead, a large area near the seaside town that had been secured by the Allies in January. They arrived there on March 26. He wrote to Coach Sakamoto from Anzio: “There’s a creek by our camp…Just seeing the water makes me homesick for the islands.”

On May 24, the 100th made its breakout from Anzio and was engaged in the battles south of Rome. After the fall of Rome to the Allies, on June 5 the 100th was sent to a large bivouac area in Civitavecchia, 50 miles north of Rome. While there, they met up with the newly arrived 442nd RCT and became their “1st” Battalion, as the 442nd’s 1st Battalion had been depleted by sending three waves of replacements to the 100th in the preceding months and by transfers out to companies in the 442nd’s 2nd and 3rd Battalions.

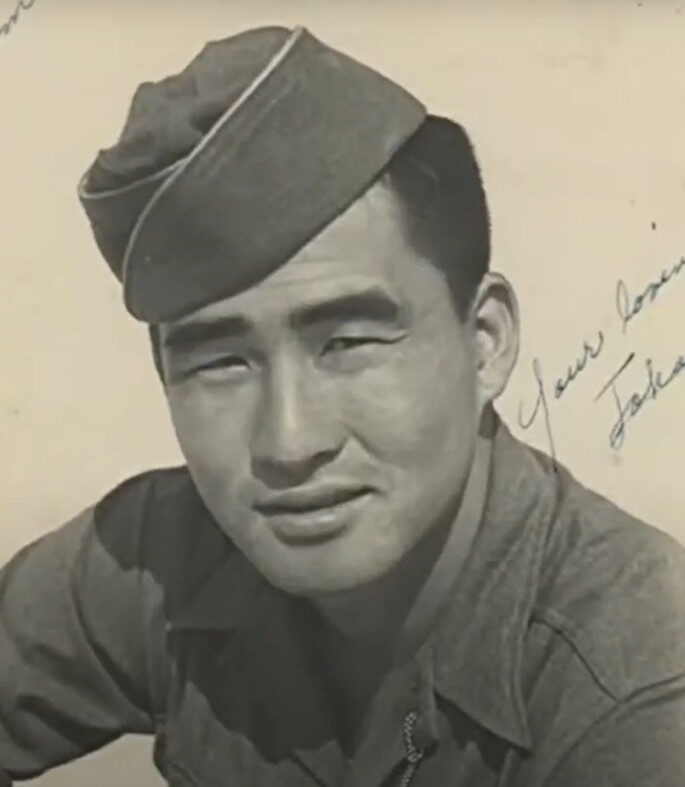

Left: Pvt. Hirose during the war

The 100th and 442nd first went into combat together on June 26 near Suvereto. After nearly a month of intense fighting, the Combat Team was pulled from the front lines and sent to a rest area near Vada on July 21. At some point, Private Hirose had contracted dysentery and was sent to the hospital. He jokingly recalled later, “I think I ate too many green apricots or something.” While in hospital, he was called to Division Headquarters to sign up for the Allies Olympic Games to be held in Rome the end of July. He had only one week to practice as a member of the Fifth Army Swim Team. Under the coaching of Captain (Doctor) Katsumi Kometani (100th Battalion Medical Detachment), the 442nd team won the Mediterranean Theater title against former Olympic and National champions from all the Allied forces in the theater. Team members were: Pfc. Charles Oda (Regimental Headquarters), Pvt. Halo Hirose, Pfc. Yujiro Takahashi (B Company), Pfc. John Tsukano (D Company), Pfc. Kenneth Oshima (B Company), Tech/5 Itsuki Oshita (100th Battalion Headquarters), Tech/5 Thomas Tanaka (K Company), Pvt. Hideo “Mike” Mizuki (E Company), Tech/5 Robert Iwamoto (Regimental Headquarters), Pvt. Joseph Yasuda (M Company), Corp. Tsugio “Shangy” Tsukano (M Company, who had been wounded in his left arm), and Pfc. Asami “Ace” Higuchi (2nd Battalion Headquarters). Hirose won first place in the following events: 100-meter backstroke, 100-meter freestyle, 200-meter freestyle, and 300-meter medley relay team (with Pvt. John Tsukano and Pfc. Steve Brinza of the 85th Division). Contestants at the games included Army and Navy personnel of all the Allied nations, with men being flown in for competition from combat areas. As the newspapers said: “It was as close as you’d even want to come to an Olympics.”

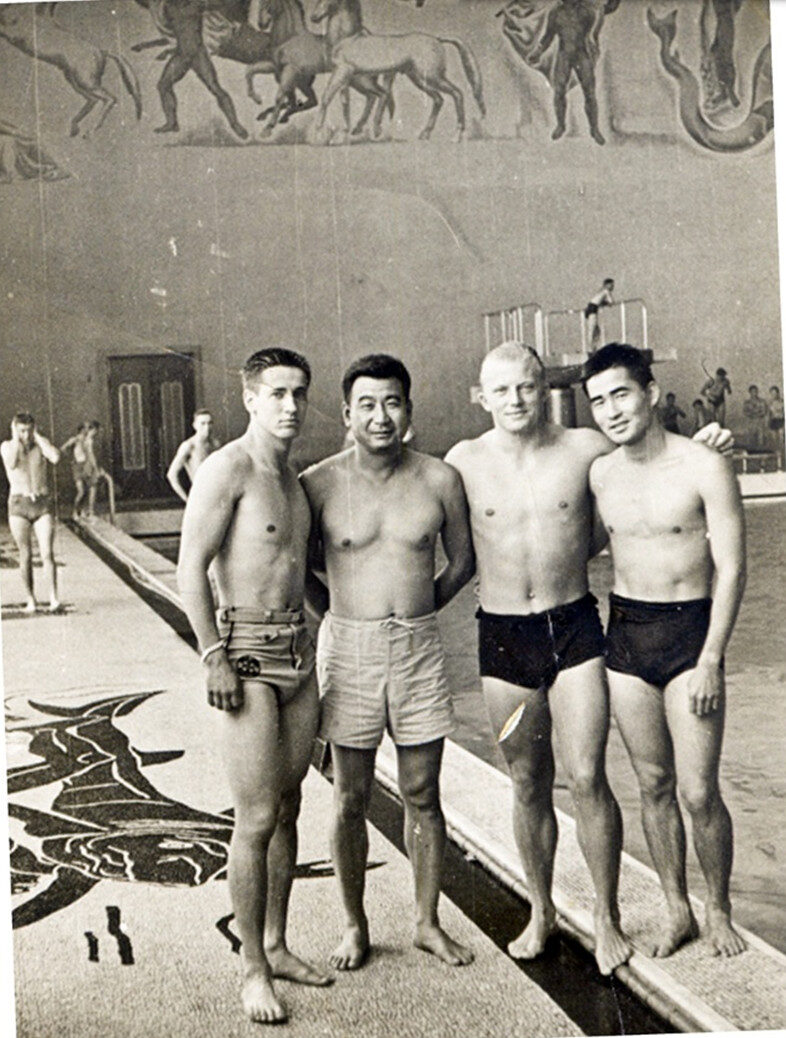

Below: Il Foro Mussolini Natatorium, Rome, July 1944, with Coach Kometani (2nd from left) and team captain Halo Hirose (far right)

On August 16, the 442nd returned to the front lines at the Arno River and they continued to push the enemy north. In late September, the 442nd was sent to Naples for shipment to France, where they joined in the Rhineland-Vosges Campaign. They arrived at Marseilles on September 29 after a 2-day voyage, and bivouacked at nearby Septèmes prior to traveling over 500 miles north by truck or rail boxcars to the Vosges Mountains. The weather was cold, wet, snowy, and miserable, as the men fought in the heavily wooded forests still in their summer uniforms. They were subjected to living in wet foxholes, and incoming artillery raining down on them in “tree bursts.”

Hirose was in combat for the next month during the bitter fighting to liberate the important road and rail junction of Bruyères, neighboring Biffontaine and Belmont, and the “Rescue of the Lost Battalion,” the 1st Battalion, 141st (Texas) Infantry that had advanced beyond the lines and was surrounded on three sides by the enemy. Finally, on November 17, the 442nd was relieved from the front lines after 25 days of heavy fighting, and sent to the south of France. There, they could rebuild to full combat strength while participating in the Rhineland-Maritime Alps Campaign, which was mostly a defensive position guarding the French-Italian border from attack by the German Army in Italy.

During his time in the Vosges, Pvt. Hirose contracted trench foot, as did many of the 442nd soldiers. In Southern France, it worsened to the point that he could no longer put on his boots or move his legs.. He was sent to the hospital, and later moved to the Thomas M. England General Hospital in Atlantic City, New Jersey, for rehabilitation. He recovered but suffered from the effects of trench foot for the rest of his life. Our research did not reveal when Hirose returned to his unit.

The 442nd was in the Maritime Alps Campaign from November 23, 1944, until March 15, 1945, when they were relieved and moved in relays to the new staging area at Marseilles. On March 20-22, the 442nd (without its 522nd Field Artillery Battalion who were sent to Germany) left France to fight in the Po Valley Campaign for the final push to defeat the Nazis in Italy. They arrived at the Peninsular Base Section in Pisa on March 25 and were assigned to Fifth Army. The 442nd fought in the Po Valley Campaign in what was supposed to be a diversionary attack up the west coast while the main thrust of the Allies in Italy was farther east.

The 442nd relentlessly pursued the enemy in their diversionary attack, resulting in a complete breakthrough of the Gothic Line in the west. Despite orders from Hitler to fight on, the German forces in Italy surrendered on May 2, 1945, a week before the rest of the German forces in Europe surrendered.

Pvt. Hirose was with the 442nd while on occupation duties at Ghedi Airfield guarding and processing German prisoners. He later recalled that while performing guard duty of German POWs, he heard one of the prisoners call his name and recognized the soldier as Helmut Fischer, an Olympic swimmer against whom he had competed before the war in the 100-meter freestyle. Fischer had been captured by the Russians.

Pvt. Hirose was soon put to work with the Army’s team for the AAU Outdoor Championships – and promoted to Private First Class. That summer he also participated in exhibition swim meets in France and Egypt.

According to the Honolulu Star-Bulletin on August 17, 1945, Hirose was discharged from the Army on July 19 and back home working for E.O. Hall & Son in their sporting goods department.

For his military service, Takashi Hirose was awarded the Bronze Star Medal, Good Conduct Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with one silver star (for five campaigns), World War II Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal, Distinguished Unit Badge with one oak leaf cluster, and Combat Infantryman Badge. He was awarded the Gold Medal on October 5, 2010, along with the other veterans of the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team. This is the highest Congressional Civilian Medal.

On September 1, 1945, it was announced that Halo Hirose was sailing on the S.S. Matsonia for the mainland, where he would enroll as a student at Ohio State University in Columbus. In 1946, at the Big Ten Swim Championship he placed first in the 100-yard freestyle; and also first in the same category at the NCAA Swim Championship. While at OSU, Hirose was a member of Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity, on their swimming team, named All-American three times, and helped them win Big Ten, NCAA, and AAU team titles. He graduated from OSU in 1949.

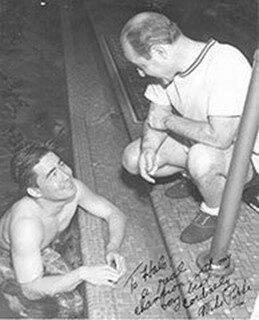

Left: Halo with Mike Peppe, his coach on the 1939 US Team in South America and his coach at OSU

In March 1950, Halo Hirose married Kiyomi Kagawa, the daughter of Takato and Isono Kagawa of Honolulu. After their wedding, they lived at 226 Lewers Street. He was employed as an adult probation officer for the Honolulu 1st Circuit Court and she was the proprietor of a dressmaking shop. Over the years, they raised one daughter, Sono. Kiyomi worked as a fashion designer for Iolani Sports Wear. Halo became attached to the Antitank Chapter of the 442nd Veterans Club and for many years played Santa at their annual Christmas party.

Right: Kiyomi Kagawa Hirose’s wedding photo

Hirose retired in 1982 as Hawaii’s Chief Probation Officer. He then took a position with Nihon Sport as a coach for their swimming team. He and Kiyomi moved to Japan and spent six years there before returning to Hawaii. Over the post-war years, Hirose started the Town Swim Club and coached the swim teams at Iolani School, Punahou, St. Andrew’s Priory, and Manoa Swim Club. According to his wife, Kiyomi, “He really enjoyed it – and the kids loved him, because he treated everybody the same, no matter if you were the slowest swimmer or the fastest.”

In 1987, Hirose was inducted into Ohio State University’s Sports Hall of Fame.

Takashi Halo Hirose died on August 24, 2002, in Honolulu at the age of 79. According to his wife, he was “the healthiest man in the neighborhood” before health issues surfaced two months earlier. Survivors included his wife Kiyomi, one daughter, two grandchildren, and sisters Harriet Uchigaki and Yaeno Hirose. He was inurned on September 9 in the Columbarium at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at Punchbowl, Section Ct5-V, Row 400, Site 428.

Kiyomi Hirose died on October 5, 2003, and was inurned with her husband.

In 2002, Hirose was posthumously inducted into the Hawaii Swimming Hall of Fame. In February and March 2010, the Hawaii Theater for Youth staged a production at St. Andrews Tenney Theater entitled, The Three-Year Swim Club. One of the featured actors portrayed Halo Hirose.

In November 2013, his daughter Sono Hulbert Hirose provided the floral display that adorned the front gate of the Waikiki Natatorium in memory of her father and other Hawaii veterans for the Veterans Day ceremonies.

In 2016, author Julie Checkoway published her book, The Three-Year Swim Club: The Untold Story of Maui’s Sugar Ditch Kids and Their Quest for Olympic Glory. Halo Hirose was among the Maui swimmers featured in the book.

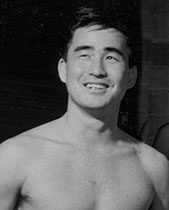

Left: Pre-war photo used for ISHOF induction

In 2017, Halo Hirose was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame (ISHOF) as a “Pioneer Swimmer.” At the ceremony held in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, his daughter, Sono Hirose Hulbert, received the award for her father. She later recalled that her father kept all his trophies in a box and did not display them in their home. He rarely spoke about what he did during the war or his career as a swimmer. Fellow Hall of Famer Sonny Tanabe said, “He gave back to the community. He did want to talk a lot to the younger swimmers and encourage them and to explain the finer points of swimming.”

Researched and written by the Sons & Daughters of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in 2025.