Soldier Story: Terry Takashi Ogawa

Soldier Story

Terry Takashi Ogawa

Technician 5th Grade

442nd Regimental Combat Team

232nd Combat Engineer Company

Terry Takashi Ogawa was brought into this world by a midwife on March 13, 1920, on a small berry farm, on Wall Street Road in Sumner, Washington. He was the second child of Jisuke George and Yasu (Hirano). Terry’s siblings were: brothers Minoru George, Samuel, Alfred, and Clarence; and sisters Taeko Betty, Elsie, and Julia.

Father Jisuke arrived in Seattle in 1907. He returned to Japan in 1913, arriving back in Seattle on March 24, 1914, on the Aki Maru. His occupation was given as “porter.” Mother Yasu arrived in Seattle on the Sado Maru, at the age of 20 as Jisuke’s wife, on September 24, 1914, from the town of Negishi, Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, the home of Jisuke’s father Chunosuke Ogawa.

Along with a long agricultural tradition, Sumner had small-town celebrations that Terry and his family participated in throughout the year – Spring Daffodil festival, Easter, 4th of July fireworks and picnic for brother George’s birthday, and Halloween. At Christmas, Terry would bring home a small evergreen tree from the hills, decorate it, and hang stockings with small gifts for his younger siblings. On New Year’s Day the family would eat Japanese food and pound mochi.

In 1920, the family lived on their berry farm on Wall Street Road in Sumner. By 1930, they were living on their own farm on Gravel Road. Hoboes were hired to work on the farm, and the family marked the corner yard post with chalk to alert other hoboes that there was work there. Indians were also hired and told Terry that the sound of the wind was the crying from the ghosts of their people and what they had lost.

Terry loved the farm life and all it meant: waking up to the rooster, playing with Billie the workhorse and Billy the collie, roasting potatoes, marshmallows and wieners on hot coals in the summer, smelling the root beer made from extract in the barn, and raking and playing in the yellow, orange, and red leaves with the pleasant smell of burning leaves from the huge maple tree in the fall.. Hand-puppet, colored-light shows in the neighbor’s barn were fun. Terry was a good cook and loved making Denver omelets from their farm fresh chicken eggs.

The Great Depression came and lasted through the 1930’s and the farm which made a lot of money from hops was lost.. The family lived in other places and did the best that they could to survive. An artist came to the high school to make faces out of names of people and he misheard Takashi as “Ticky” – and that is how Terry got his nickname. He graduated from Sumner High School in 1938.

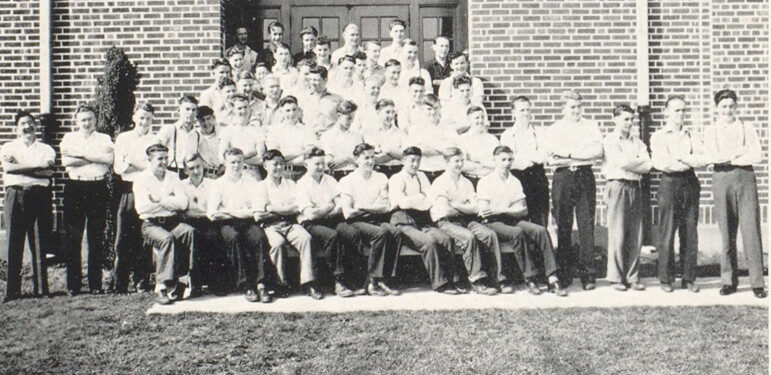

Above: Junior class photo, 1937; Ogawa is front row, 7th from the left

In March 1939, Terry was a member of the National Youth Association (NYA) Camp and worked at their administration building on the Nisqually River near LaGrande. While there, several of the young men went out on a photo shoot and separated to cover more area. One of them did not return at the appointed time and the others searched for him for two hours. Others joined the search and his body was found at the foot of a canyon during the night. The experience was devastating to Terry.

In 1940, Terry was living with his family at 1721 Hubbard Street in Sumner. Both parents were farm laborers and eldest son George was a radio operator for an NYA project. George was fortunate and graduated with an engineering degree from Washington State University in Pullman before the war started. Terry had begun classes at the University of Washington, but changed to the Forestry School at Pack Forest, south of Tacoma, later owned by the University of Washington and managed by its School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. He had a happy-go-lucky personality, loved camping and fishing at Lake Tapps, and often took his brothers into the mountains. Terry had aspirations to be a forest ranger.

Terry Ogawa signed his draft registration card on July 1, 1941, Local Board No. 1, Pierce County, Washington. He lived with his family in the Hubbard Street home, was a student, and his father was his point of contact. He was 5’3” tall and weighed 125 pounds. One of his brothers later recalled that the threat of war disrupted his education plans. Terry would eventually never fulfil his dreams of becoming a forest ranger. He dropped out of school and went to work to help his family financially. He bought a Ford Model T car with a rumble seat with money that he saved working for 20 cents an hour for the neighbors and selling the pelts of the muskrats he caught by the creek. Terry left for California looking for work.

The United States declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. With fears of sabotage and espionage, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, that authorized the Secretary of War to exclude people in designated military areas, which led to the forced mass relocation of about 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans on the west coast with loss of their homes, belongings, businesses, and lives and placed into internment camps. Terry returned home from Stockton CA because of the Presidential Executive Order and found the FBI watching 24 hours a day.

In the spring of 1942, the Ogawa family and other families were evacuated and taken in jeeps and buses to the Puyallup Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) Assembly Center, located on the Western Washington Fairgrounds, just a few miles from their home in Sumner. Before they used to come here and have fun at the Puyallup County fair-riding the roller coaster, eating cotton candy, and looking at the distorted images of themselves in the mirrors of the funhouse. Now the family lived in two crowded rooms and slept on bags filled with straw covered with itchy army blankets. Terry made a gunny sack playhouse with boxes for a table and chairs for the younger ones where they had tea parties and ate cucumber sandwiches, fried potato sandwiches, watermelon, and their favorite Boston Cream Pie. Playing cards and playing baseball helped pass the time. Reville was played in the morning and the soulful sound of Taps was played at night.

On August 16, the Ogawa and other families at Puyallup were loaded on trains bound for incarceration at Minidoka War Relocation Authority (WRA) Interment Camp, a remote, barren, desolate place about 16 miles from Jerome, Idaho. The internment camp was surrounded by barbed wire fences, and the perimeter was secured with guard towers manned by military police. According to his sister Betty, they were one of the first families at Minidoka and they were assigned to live in Block 1. Terry worked in the garage repairing trucks and other vehicles.

Almost nine months later on May 6, 1943, Terry was released to Camp Douglas, Salt Lake City, Utah, so he could enlist in the U.S. Army on May 7. His residence upon entry into service was listed at Minidoka as Block 1, Barracks 3F&H, Hunt, Idaho. He was listed as having completed high school. His civilian occupation was given as “Semi-skilled mechanic and repairman, motor vehicles.”

Betty said that he was one of the first men from Minidoka to volunteer. His enlistment was reported in the Tacoma Sunday Ledger-News Tribune on May 16 as being among eight former Puyallup Valley youths from Minidoka Resettlement Camp to join the Army.

Sister Betty was released from Minidoka on September 5, 1942, to go to Chicago, Illinois, for work. The rest of the family was released in 1945 to go to Kenosha, Wisconsin: his father on January 17 and everyone else on March 20, 1945.

Terry Takashi Ogawa was enlisted into the U.S. Army on May 16, 1943. He was sent to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, where he was assigned to the 442nd RCT’s 232nd Combat Engineer Battalion. His son later recalled that this was a good fit for his father as “he was mechanically inclined.”

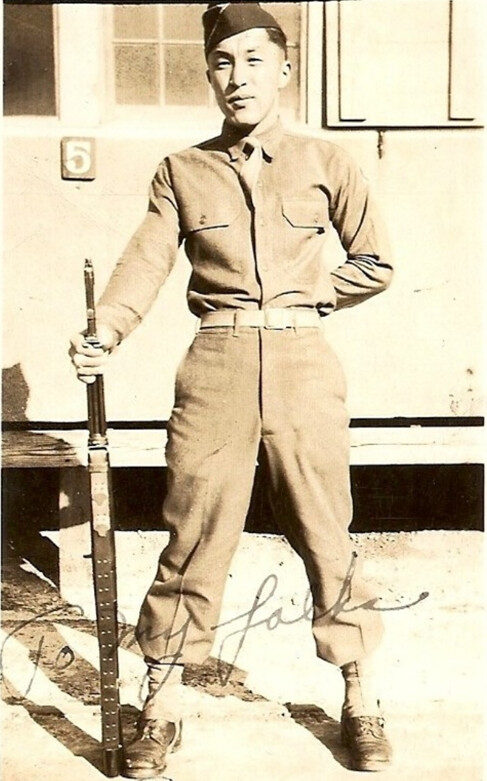

Right: Private Ogawa at Camp Shelby, January 1944

The 232nd Combat Engineer Company, an original unit of the Combat Team, trained next to the infantry and field artillery and learned the same things – the fundamentals of soldiering. But they were also learning to ply their specific trades. The engineers played dangerous games with high explosives – building bridges and blowing them up, building and repairing roads, removing enemy roadblocks, and laying and destroying minefields. They learned how to operate their machines: metal detectors, chainsaws, and bulldozers. There were 204 enlisted men plus seven officers in the 232nd over the course of their service.

Basic training ended on August 23 and was followed by five days of intensive testing from Third Army teams. The RCT rated Excellent in physical fitness and Very Satisfactory in all other departments. Next followed a respite of short furloughs to enable men to visit cities such as New York, Chicago, or New Orleans, or to go west to visit their families in internment camps. Terry used this time to visit his family at Minidoka.

Platoon and company training began about October 20 and lasted about one month. This was followed by the final phase of training – combined training. Part of this time was spent by the 232nd Engineers demonstrating their abilities in support of the infantry. Several times the regimental commander called on the engineers to execute demolitions and then dig in as infantry to defend them so as to delay an enemy advance.

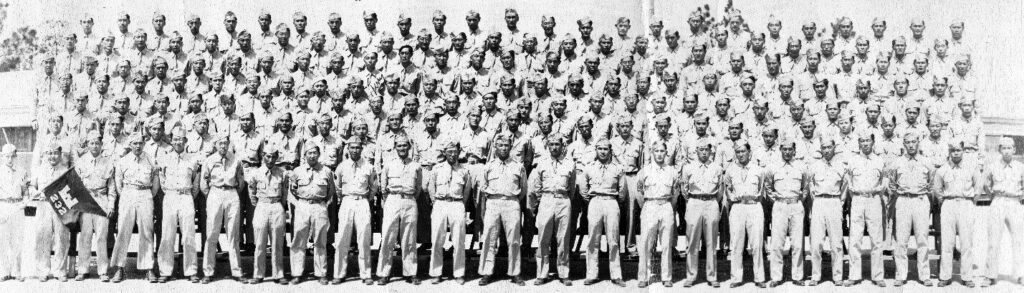

Below: 232nd Combat Engineers at Camp Shelby June 1943; Ogawa is 5th row down from the top, 9th from the left – he wrote his name above his head

The entire Combat Team next participated in “D” Series maneuvers beginning on January 28, 1944, in the DeSoto National Forest, Mississippi. The 442nd and the 232nd were attached to the 69th Infantry Division for the maneuvers.

Finally, on April 22, 1944, the Combat Team departed Camp Shelby for Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia. On May 2, they sailed in a convoy of over 100 ships from Hampton Roads for the Theater of War, arriving at Naples, Italy, on May 28. The 232nd Combat Engineers sailed on the Liberty Ship S.S. Thomas Cresap along with the 442nd’s 206th Army Ground Forces Band. They were assigned to bunks in Hold No. 2. During the weeks at sea, the 206th Band entertained with concerts on deck and even in the below-deck quarters in inclement weather.

The 442nd entered combat near Suvereto, north of Rome, on June 26 in the Rome-Arno Campaign. They successfully pushed the enemy north along the western part of the peninsula. They remained in Italy until departing for southern France. The 232nd sailed on the U. S.S. Samuel Chase on September 26 and debarked at Marseilles on September 29.

After arriving in southern France, the Combat Team headed north and fought in the Rhineland-Vosges Campaign beginning on October 13. This was the most bitter fighting they had encountered. The 232nd Combat Engineers were attached to the 111th Engineer Combat Battalion of the 36th Infantry Division. They endured almost continuous rain and snow, and yet between October 23 to November 11 the men accomplished the engineering feat of constructing a supply road out of what was a mountain trail that rose 1,000 feet off the floor of the Laveline-Corcieux Valley of the Vosges Mountains. The road enabled supplies to be taken in and casualties to be carried out. This road led to the 36th Division outflanking the Germans and pursuing a disorganized enemy to the banks of the Meurthe River.

From October 26 to October 30, they participated in the famous rescue of the trapped “Lost” Battalion – the 1st Battalion of the 141st (Texas) Infantry Regiment – by sweeping the roadways for mines and keeping them clear for traffic. The 232nd Combat Engineer Company was awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation for their actions in the Vosges Campaign.

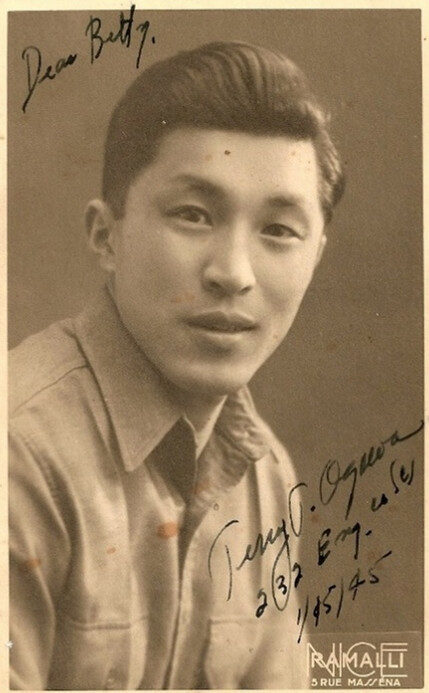

Due to devastating casualties that put the 442nd below combat strength, they spent the months of late November 1944 through March 1945 in the Rhineland-Maritime Alps Campaign. This was a mostly defensive position to guard against enemy incursion along the French-Italian border. During the Maritime Alps Campaign, Ogawa visited Ramalli photo studio, 5 Rue Massèna in Nice, where he had his photo taken to send to his sister Betty.

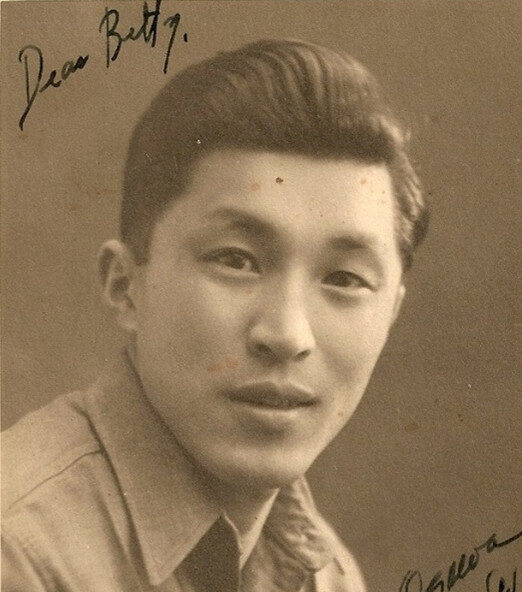

Photo left: Terry in Nice, January 15, 1945

While in the south of France the men often had passes to visit Nice where they could relax. For this reason this was nicknamed the Champagne Campaign.

After rebuilding their numbers as replacement troops arrived to the 442nd from the US, the 232nd was sent with the 442nd RCT back to Italy to fight in the Po Valley Campaign. The 232nd Engineers debarked on March 23, 1945, on the LST 907 for Italy. The 442nd was engaged in combat from April 4 until the German forces in Italy surrendered on May 2. Once again, the 232nd Combat Engineers were awarded a Distinguished Unit Citation as part of the Combat Team for their part in breaking the enemy’s heretofore impregnable Gothic Line.

Terry was in Italy during the occupation. His brother recalled that he came home on a ship before his discharge on December 17, 1945, at the Army Separation Center, Camp Grant, Illinois. His brother noted that Terry was no longer happy-go-lucky, and did not smile or laugh as much – war had changed him. Terry said that the scariest part of his job in the Army was defusing booby traps at night. Terry was home and everyone was overjoyed. As always, he would say as he hugged the family or shook hands, “Hi, how’s things.” He brought back gifts for the family – a Swiss watch for his father, jewelry for his sisters, and a complete set of china with an apple blossom design for his mother.

For his military service, Tec/5 Terry T. Ogawa earned the: Good Conduct Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with four bronze stars, World War II Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal, and Distinguished Unit Badge. He was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal on October 5, 2010, along with the other veterans of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Conferred by the U.S. Congress, the award states: “The United States remains forever indebted to the bravery, valor, and dedication to country these men faced while fighting a 2-fronted battle of discrimination at home and fascism abroad. Their commitment and sacrifice demonstrates a highly uncommon and commendable sense of patriotism and honor.ˮ

Terry settled in Chicago, where he met Masae Nishimura (born July 1920), the daughter of Shinkichi and Ume (Yamagata) Nishimura, originally from Seattle. The Nishimura family had also been incarcerated at Minidoka, Block 28. After their release, they settled in Chicago.

On April 9, 1950, Terry and Masae were married in Chicago. She had also been incarcerated with her family at Minidoka. Since he worked as a auto mechanic, the family recalls that his sister Betty scoured his hands with powder and bleach before the wedding.

Below: Ogawa wedding photo

The newlyweds settled in Chicago at 914 West Belle Plaine Avenue. In 1950, Terry was employed as an auto mechanic and Masae was a stenographer at a general wholesale company. Over the years they raised a family of two sons. Terry earned a machinist certificate and numerous auto mechanic dealer certifications. His brother later recalled:

He helped the family out more than anyone else by helping the folks buy a 6-unit apartment building on Millard Avenue in Chicago and furniture. While away, he had sent home a check every month. At that time, he went to work as a mechanic at a DeSoto dealer on 47th Street.

Terry and Masae lived in the same building as Masae’s sisters on North Ashland Avenue on the North Side for about 30 years from 1954 to about 1985 when the building was sold. They eventually moved to Jefferson Park in 1987 for the last 10 years of his life. He was a retired certified auto mechanic for Chrysler Motors.

Terry loved and missed the outdoors and the small town atmosphere of his childhood years in Sumner, so he bought a cabin about 3 hours away by the shores of Lake Puckaway in Wisconsin. He’d pack up the family after work on Fridays for the weekend, stop at the Big Boy Restaurant, up early Saturday morning for a hearty breakfast cooked by Masae, work on and around the cabin, shop at the Piggly Wiggly, and dinner at Sharenberg’s White Lake Resort. Later, after selling this home, he’d spend time at his son’s vacation home in nearby Green Lake, Wisconsin where he loved cutting the lawn with the riding mower and smelling the freshly cut grass that reminded him of his boyhood and just relaxing.

Terry T. Ogawa remained faithfully married for almost 46 years until his death on March 14, 1996, in Chicago. His funeral was held in the Lakeview Funeral Home at 7:30 p.m. on March 18. Terry was buried in Oakhill Annex, Montrose Cemetery, Chicago, in the Japanese section. Survivors included his wife Masae, sons Timothy and David, and grandchildren Kimberly and Kevin. Other survivors included brothers George, Sam, Alfred, and Clarence, and sisters Mrs. Betty Hansen, Mrs. Elsie Koga, and Mrs. Julia Tokiwa. Masae died on June 5, 2011, and was buried next to her husband.

Researched and written by the Sons & Daughters of the 442nd RCT in 2025 with information from his son Timothy Ogawa, who is a member.