Minoru Masuda

Technical Grade 3

442nd Regimental Combat Team

2nd Battalion, Medical Company

Minoru Masuda was born on April 10, 1915, in Seattle, Washington. His parents Sahei and Kika (Sonoda) Masuda had emigrated from the village of Nanataki, Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. Sahei arrived in the US on March 27, 1908. He was listed as a farm laborer. His wife, Kika, emigrated as a laborer in March 1909 on the ship Aki Maru.

Minoru had two brothers, Satoshi and Hakaru, and two sisters, Kiyoko and Mitsuko.

Min, as he was known, attended Franklin High School. He participated in the Art Club, Spanish Club, and Honor Society. In his 1930 high school yearbook it is written that “Minoru knows his carrots.” During those times, the phrase “He knows his onions” meant that a person was knowledgeable.

At the University of Washington, Minoru achieved a Bachelor of Science in 1936, and was selected to be on the Phi Sigma honorary society for his studies in pharmacy. In 1938, he received a Master of Science specializing in pharmacy.

Min married Hana (Koriyama) Masuda on May 28, 1939 at the Japanese Baptist Church in Seattle. In 1940, Min and his wife lived at 1902 Jackson Street and he worked at the Hikida Furniture Store as a clerk and general helper.

Min’s father and the Masuda family managed and worked during the 1930s at the historical Freedom Hotel located at 506 1/2 Maynard Ave. The building is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places as part of Seattle’s Chinatown Historic District.

Min registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, at Local Board 9 at the Field Artillery Armory in Seattle. He was 5 feet 9 inches tall and weighed 142 pounds. His wife, Hana M. Masuda, was his point of contact.

When Pearl Harbor was bombed, Min’s family was still living at and managing the Freedom Hotel. The Seattle Daily Times stated on December 12, 1941, five days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, that Min’s father, “Sahei Masuda, Japanese proprietor of the Freedom Hotel, 506 ½ Maynard Ave., reported to police that at about 9 o’clock last night two nozzles were cut off the establishment’s fire hose.”

In May 1942, Min and his wife Hana, with identification number 11704 attached to their lapels, left their home for incarceration. In his words, “We took ourselves and what we could carry to Seventh and Lane streets to await the bus.” They were evacuated to the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) Assembly Center, known as “Camp Harmony.” It was located on the grounds of the Western Washington Fairgrounds in Puyallup. His immediate family also went to Puyallup in May 1942; however, his younger brother, Hakaru, remained behind – hospitalized with tuberculosis. Hakaru would die the next year isolated in Seattle, away from his family.

Three months later, Min and his family were incarcerated on August 1942 at the Minidoka WRA Internment Camp near Hunt, Jerome County, Idaho. They were assigned to Block 16, Barracks 5, Unit F.

Minoru would later write – “The physical hardships we could endure, but for me the most devastating experience was the unjust stigmatization by American society, the bitter reminder that racism had won again over the Constitution and the Bill of Rights…simply because of our blood. It was galling, infuriating, and frustrating.” He wrote that the “stigmatization of being branded disloyal and imprisoned evoked a sense of shame…because of its sanction by American society.”

While at Minidoka, Min was shocked to hear that the government would be recruiting from the camp to form a segregated regimental combat team. He would write many years later – “How could the government and the army, after branding us disloyal…and imprisoning us in barbed wire concentration camps, how could they now ask us to volunteer our lives in defense of a country that had so wrongfully treated us?”

“I wrestled with the problem…I was older than the others. I was married, more mature, and had more responsibilities…the possibility of death in the battlefield was real, and, in the Nikkei context, almost expected. I admit, too, despite all the trauma, that an inexplicable tinge of patriotism entered into the decision to volunteer.”

Min was among 308 Japanese American men at Minidoka who enlisted in the U.S. Army. He left Minidoka on May 12, 1943, and enlisted at Camp Douglas, near Salt Lake City, Utah, on May 27, 1943.

He was sent to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, for his initial basic training with the combat team. Due to his pharmacy background, Min also spent August and September in 1943 at the O’Reilly General Hospital in Springfield, Missouri for special medical training. He was assigned to a Medical Company and was detached to serve as a medic (Technical Grade 3) for the 2nd Battalion.

While training at Camp Shelby, Min received word of his younger brother, Hakaru’s death from tuberculosis. Min would later write:

“When the message came, I walked into the jackpine woods, thought about how I’d loved him and how he had died all alone in the that miserable place without any of us at his side and I cried in that anguish and swore anew at those who had allowed this to come to pass.”

Min and the Combat Team left Mississippi in late April 1944, via rail for Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia, which was serving as a staging area for being shipped overseas. Min spent much of the next seven days administering typhus and smallpox shots to the troops. On May 1, they left Camp Patrick Henry on a shuttle rail to the nearby Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation, whereupon they boarded a Liberty ship. This ship accommodated the soldiers in 5-high bunk-bed style structures. The voyage, navigating in a defensively protective zig zag movement, lasted four weeks.

Min, and most of the 2nd Battalion, arrived in Oran, Algeria, on May 28, 1944. Their ship had been diverted in order to drop off cargo. On June 6, they embarked from Mers El Kebir, Algeria, aboard the British troopship HMT Samaria, arriving at Naples, Italy, where the bulk of the 442nd had arrived the end of May.

In June, Min and the 442nd were joined by the 100th Battalion, consisting of former National Guardsmen from Hawaii. They stayed in Italy, fighting from June through September 1944 in the Rome-Arno campaign.

Min would later write about the first day in combat under a “baptism of fire” as a medic on June 26th, 1944. He described that his combat team had got caught with no cover.

” [They] were pitifully pinned down …terrifying shells came in clusters that sent fragments whining, shaking the earth and clipping branches and leaves overhead that fell down on us… Thank God you’ll never know the abject terror that we knew in those first moments, nor come to realize just how deep a love one has for life…a call came down for medics from above the gully and I worked up past the huddled men to gaze at our first casualties. Two men were dead – one our Captain and the other a PFC…four more lay injured. Realizing the inadequate protection of this gully, we picked up the casualties after first treating these injuries and staggered up the rocky gulch for a hundred yards, which deepened at one portion…took better stock of their injuries. All were litter cases, and two were badly hit. We piled rocks around them [to protect them] from any flying missiles.”

Beginning in in October 1944, Min and the Combat Unit entered the Rhineland-Vosges Campaign. In dense woods with foggy and freezing conditions, the 442nd battled ferociously in the Vosges Mountains in northeastern France. They succeeded in rescuing the ‘Lost Battalion’ (1st Battalion, 141st Infantry of Texas) which had been isolated by German forces. The 442nd suffered 842 casualties during their rescue of the 211 soldiers of the ‘Lost Battalion’

Above: Italian citizens scavenging for food from 442nd garbage

Through the Rhineland-Vosges campaign and through other campaigns, Min witnessed and encountered civilian populations. He wrote to his wife, that, “so many are hungry…all the food shops are bare of goods…and I mean really bare, absolutely bare…and the people are out hunting for food.”

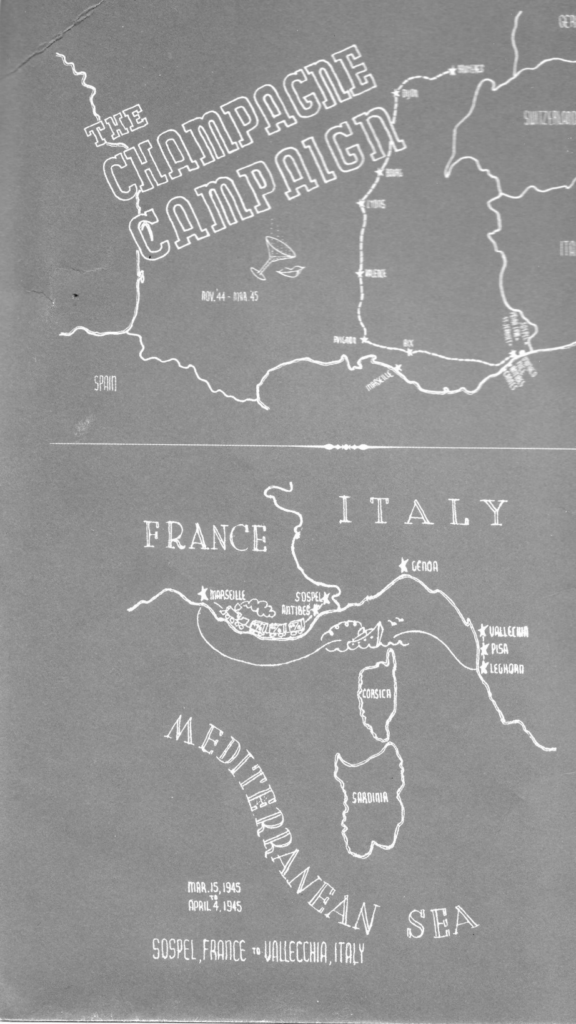

After the Rhineland-Vosges Campaign, Min and his fellow 442nd troops were stationed on the French Riviera near Nice, France, from December 1944 through March 1945. Although there were occasional skirmishes, the men took advantage of opportunities in nearby Nice. This was known as the “Champagne Campaign.” Min wrote to his wife – “It hardly seems possible that tempus can fugit so fast.”

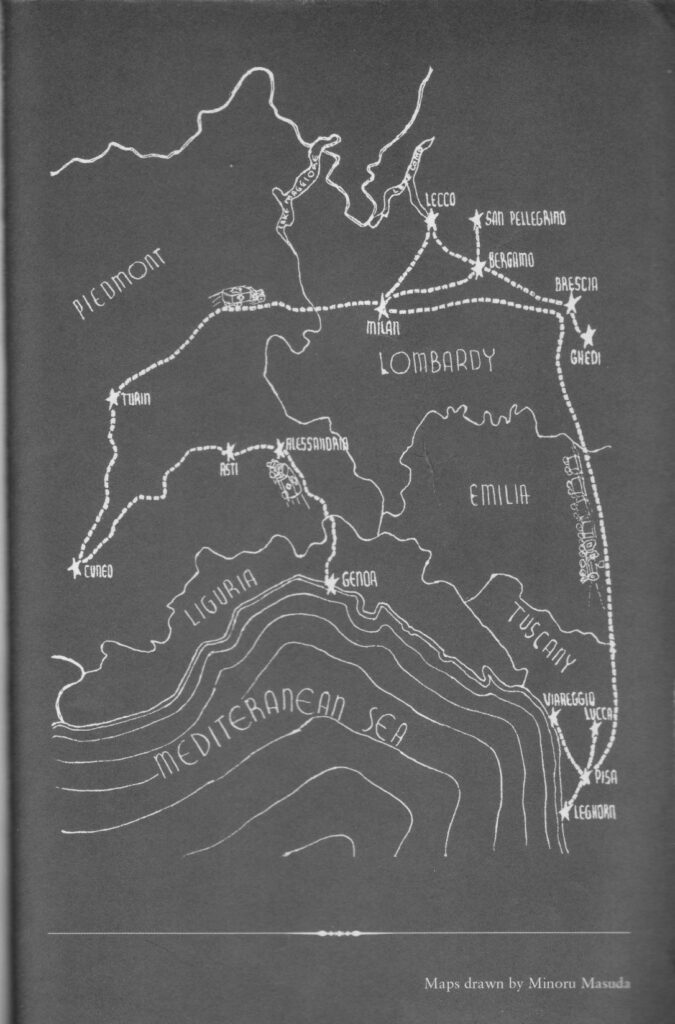

In April of 1945, Min and the Combat Team returned to Italy and participated in the Po Valley Campaign, which was made very difficult due to the mountainous terrain. As the Germans retreated, the 2nd Battalion tracked them northward through Italy.

Photo left: Self -portrait drawn by Min upon returning to Italy.

After the surrender by the Germans on May 2, 1945, the 442nd processed eighty thousand German POWs at an airfield near Ghedi, Italy.

Above: German Soldiers surrendering to Min. He took custody of them while in his shorts and socks. April 1945, Vallechia vicinity, Italy.

Minoru was one of the last of the original 442nd volunteers to leave Europe. He was discharged and finally reached home on the last day of the year, December 31, 1945. He had spent approximately one year and seven months of combat tour in the European theater.

For his service, Technician Third Grade Minoru Masuda was awarded the Bronze Star Medal, Good Conduct Medal, American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with four bronze stars, World War II Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal, Distinguished Unit Badge, and Combat Medic Badge. He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal on October 5, 2010, along with the other servicemen of the 100th/442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team. This is the highest Congressional Civilian Medal.

Having returned to Seattle after the war, Min’s family began running a small hotel again; Min would write:

“My father was now a shadow of his former self, not the strong, authoritarian, dominating figure of old – he was not broken but he was surely bent. He was much less a man than before, no longer the head of the household. He came down with tuberculosis, went into the sanatorium, even as I did a year later. I saw him on the day before he died, both of us on parallel wheeled stretchers. How could I tell this dying man, my father, of what I now felt – language lay as a stone wall between us. How could I tell him of the respect and love and appreciation for all he had done for all of us. There could only be the unspoken message of the touch of hands and the meeting of the eyes.“

Some years after his father’s death, Minoru and his wife Hana would raise two children.

In 1952, Minoru achieved his PhD in Physiology and Biophysics at the University of Washington (UW). He was elected to the Rho Chi Honorary Society for pharmacy.

As a UW faculty member, he worked in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences in the School of Medicine. He had expertise in an array of biological, psychological, and sociological sciences. He largely focused his research on psychophysiology and psycho-endocrinology. For example, he researched the relationship between stress and illness. He would present the results of his studies at conferences such as the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

During the sixties and seventies, Min was gained prominence as a spokesman for minority causes. Active in the Japanese American Citizens League, he served as president of the Seattle chapter in 1971, and was Chairman of the National J.A.C.L. Nisei Retirement Committee. He was also a member of the Asian American Task Force of the Seattle Community College District, the Nikkei Retirement Coalition, the Nisei Veterans Committee, the Asian American Counseling and Referral Service, and the Asian Americans for Political Action.

He was chairman of the Pride and Shame Traveling Exhibit and Program from 1973 to 1975. He served on the King County Mental Health Board, the Washington State Advisory Committee to the Department of Social and Health Services, and the United Way Mental Health Committee.

In 1980, Min testified before the United States Civil Rights Commission, arguing in favor of monetary compensation for the internees and survivors of the internment of Japanese Americans during World War Two.

In 1980, the year of his death, Min received the Charles E. Odegaard Award for his personal generosity and commitment to the equal opportunity and affirmative-action program at the University of Washington. He also received the Community Achievement Award from the Seattle Urban League.

Posthumously, he was honored as the Japanese American of the Biennium in Humanities and Education by the National Japanese American Citizens League in 1980.

Minoru Masuda passed away on June 12, 1980, at the age of 65. His funeral was held at the Seattle First Baptist Church on June 16. He was buried in the Evergreen-Washelli Cemetery in Seattle. Hana died in 2000, and was buried next to him.

Their names are engraved on black granite bricks on the Nisei Veterans Committee Memorial Wall in Seattle: Minoru is in the Armed Services Section: Brick #3473; Wall location: Column 28, Row 2. Hana is in the Internment Section: Brick #3472; Wall location: Column 55, Row 5.

Above: Min writing to Hana while leaning against the ruins of a house in Italy; this photo is on the cover of their book.

In 2008, Letters From the 442nd: The World War II Correspondence of a Japanese American Medic was published. The book, edited by Hana with Dianne Bridgman, contains excerpts of letters written by Min to Hana.

Below: Map hand drawn by Minoru Masuda

Below: Map hand drawn by Minoru Masuda

Researched and written by the Sons & Daughters of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team in 2021.

Sources consulted:

Letters From the 442nd, The World War Two Correspondence of a Japanese American Medic, University of Washington Press, 2008

Minoru Masuda Papers, University of Washington Archives

Seattle Daily Times Archives